The Dhandho Investor

Introduction

About the book

The Dhandho Investor lays down the powerful and comprehensive framework of value investing which is straightforward and accessible for an individual investor. This book refines the Dhandho capital allocation framework of the business by perceptive Patels from India and illustrates how they can be successfully applied to the stock market. The Dhandho method expands on the principles expounded on by Benjamin Graham, Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger. Any investor who embraces the framework is bound to enhance results and soundly beat the markets and most professionals.

About the author

Mohnish Pabrai is an Indian-American investor and businessman. He is the Managing Partner of Pabrai Investment Funds, which was modelled after the original Buffett Partnerships in the 1950s. Since its inception in 1999, Pabrai Funds have delivered annualized net returns of over 28%. He has been favourably profiled by Forbes and Barron's. He has also made guest appearances on CNBC and Bloomberg TV and Radio.

Buy the book

This book is all about value investing. How to earn a high return with low risk? The Dhandho Investor exactly teaches the same. We highly recommend you read the entire book. (affiliate link)

Patel Motel Dhandho

The author starts the book by discussing the term "Dhandho", which is a Gujarati word meaning "endeavours that create wealth" or "business". Gujarat is a coastal territory in India that has served as a nest for trade with Asia and Africa. The Patels are a subsection of Gujaratis that are mainly entrepreneurial and their ventures led to them establishing a dominant part of the East African economy by the early 1970s. In 1972, when Asians were thrown out of Uganda based on their race, an outbreak of Patel immigrants landed in England, Canada and the United States.

The Patels now form about 0.2% of the American population. Yet they own more than half of the motels in the entire country, which constitutes $40 billion in assets and $725 million in annual taxes. The author associates this to specific conditions which led the Patels to comprehend and benefit from significant upside potential and minimal downside risk in the motel business when they came to the United States.

The first Patels arrived during a recession. Motel owners were being shut out due to low occupancy rates. With just $5000 in hand, Patels could kill two birds with one stone by finding room for their families and at the same time a job by buying a motel. Since the assets were hard, banks financed 80-90% of the purchase. They lived and worked there, so no employees were required either. They offered the lowest nightly rate in the vicinity. With about 50-60% of average occupancy, the annual revenue will be $50000, out of which $5000 will be paid toward interest and another $5000 towards the principal. Another $5000-$10000 for motel maintenance and supplies will be required. Furthermore, if the family living expense is $5000, the motel will still net over $15000 yearly.

This is how the Patels could pay back their initial down payment in the first four months and elect off the entire mortgage in just three years. This introduction to low risk and high reward sets the theme for the rest of the book.

This example elucidates that high risk is not the key to higher reward. It also explains how to invest in a simple existing business. It is an introduction to low risk and high reward and sets the theme for the rest of the book.

Manilal Dhando

To dismiss the idea that the story described in the previous chapter was merely a consequence of fortunate timing and luck, the author describes another winning entrepreneurial venture where the risks were low and the potential upside was high. It is about Manilal Patel, a man who immigrated as an accountant but could not secure a job due to his broken English.

For several years Manilal worked for minimum wage, gradually building wealth while searching for a business to own and operate. For twenty years, he worked around the clock and began to invest in residential real estate. After 9/11, he got the break he was waiting for. The hotel market was suffering once again because travel was down. Manilal managed to take advantage by finding some partners and putting his capital into the purchase of Best Western hotel. Manilal borrowed $1.4 million against his house to help fund the down payment required for the hotel.

The author then goes into further detail on the different scenarios of the hotel's returns. However, the lessons he attempted to explain here in this book are clear:

1) When an incredible investment opportunity is available, a bigger investment should be made. He calls it: "Few bets, big bets, infrequent bets"

2) Take part in investment opportunities that have minimal downside risk but high upside potential: "Heads, I win; Tails, I don't lose much"

The idea behind this chapter is about doing business which has a significant upside, accompanied by a non-existent downside.

Virgin Dhandho

In the first two chapters, the author shows how hard-working immigrants with few expenditures managed to go from poverty to millions throughout their lifetimes. However, this is not the only way to make money with little risk.

This chapter is about the story of Virgin Airlines and its founder Richard Branson who is also a Dhando investor. Branson has managed to invest in several business ideas with minimal risk and yield high rewards.

Branson knew nothing about the airline business. He received a business plan that he knew must have been turned down by thousands. Branson looked forward to leasing a Boeing jumbo jet. He noticed that with a single plane, he would pay for fuel and staff wages for 30 days, but he would get paid for all the tickets about 20 days before the plane took off. The working capital requirement was low. Branson found a service gap and went for it. The Virgin Atlantic example is a pure Dhandho.

The prevailing theme is “Heads, I win; tails, I don’t lose much!”

Branson's companies don't take on the risk because they don't need investment in infrastructure. Rather, they leverage existing infrastructure or outsource to other companies that have to take on the risk. However, Branson does get the upside. With that risk-reward profile, Branson is capped as a Dhandho investor by the author.

By placing asymmetric bets Branson too follows the low-risk high certainty principle of investing. With that risk-reward profile, Branson is capped as a Dhandho investor by the author.

Mittal Dhandho

In 2005, Lakshmi Mittal was listed as the third richest man in the world by Forbes. Mutual, unlike other rich people, operated in an industry with awfully poor returns on capital - steel mills. As an owner of a steel mill, one has no control over the selling price of the products. Also, they require a constant supply of capital to be able to keep producing the end product. As a result, the steel industry has been one of the worst places to invest over the last few decades, with bankruptcies infesting every corner.

Mittal was able to revamp his steel mills into profitable steel-producing machines. Had he grown organically, he probably would never have managed to get the net worth to $20 billion. Instead, he grew by acquiring steel mills. He acquired a few mills for 10 cents which other investors had built for $1. Once he applied his operational efficiencies to the plants, he restored the value of the assets to $1 or more, thus yielding extraordinary returns on investment. Once again, Mohnish Pabrai's "Dhandho" theme echoes- the downside is minimal, and the upside is immense.

The author also takes the readers through his own experience applying "Dhandho". When he started his business, he had $30000 in cash and $70000 in credit card limits. If his investment went down, he would have to announce bankruptcy and would have lost $30000 and would have returned to his old job. In other words, his downside risk was minimum, but his upside was not. After a few years, he sold his business for several million dollars. This illustrates another example of the author’s "Heads, I win; Tails, I don't lose much" ideology.

This chapter also tells that every once in a while, one encounters overwhelming odds in his favour. In such situations, they should act decisively and place a large bet.

The Dhandho Framework

While the low-risk and high-reward businesses portrayed in the first four chapters differed in type, they did share common features. These similarities form the basis for the rest of the book, where the author talks about these features in detail:

1. Buy an existing business: Each of the businesses described in the first four chapters had defined business models and nothing new was invented. Each had a long history of operations that could be evaluated.

2. Buy businesses in simple industries with a low rate of change: All the businesses described were essential and were not getting replaced. Motels and hotels will always be in demand because travellers need a place to sleep and refresh themselves.

3. Buy distressed businesses in distressed industries: The most favourable time to buy a business is when it is unloved and hated. Under such circumstances, the odds are high that an investor can pick up assets at steep discounts to their underlying value.

4. Buy businesses with a durable competitive advantage- The moat: A company's moat refers to its potential to maintain the competitive advantages that help it repel competition and maintain profitability in the future. This advantage can come from being a low-cost brand to having captive customers. Papa Patel’s, Manilal’s, and Mittal’s moats were developed by being the lowest-cost producer.

5. Bet heavily when the odds are in your favour: In all the businesses described, the investor did not act for many years, but when the opportunity was clear and the odds in their favour, they acted decisively and placed a large bet.

6. Focus on arbitrage: Arbitrage is an attempt to make a profit by capitalizing on price differences in identical or related financial instruments. In all cases, the investors saw a disparity between price and value, which they exploited.

7. Buy businesses at big discounts to their intrinsic values: when an asset is bought at a steep discount to its underlying value, the odds of a permanent loss of capital are low, even if the future is worse than anticipated.

8. Look for low-risk, high-uncertainty businesses: The scepticism leads to severely depressed prices. Papa Patel’s motel purchase had low risks associated with it. However, the outcome had substantial uncertainty attributed to it. Even if the gas prices continued to stay high or the recession continued, Papa Patel would still be the low-cost provider. He’d still be proficient to charge less and get higher occupancy. He has a relatively high uncertainty compared to very low risk with the motel investment.

9. It's better to be a copycat than an innovator: Invention is a risk, but scaling carries a far lower risk and substantial to great rewards. Papa Patel simply followed what the other Patels did. He too did not innovate. He just minimized the cost naturally by using his family as employees.

To summarize, the Dhandho framework is to:

- Buy an existing business

- Invest in simple industries

- Buy distressed business in distressed industries

- Buy business with durable moats

- Bet heavily when the odds are in your favour

- Focus on arbitrage

- Look for low-risk, high-uncertainty businesses

- Invest in copycat than an innovator

Dhandho101: Invest in Existing Businesses

Of all of the options of asset classes that are available for investment, the author asserts that common stocks have proven to deliver the best returns. Even though investors have the option of buying and selling individual businesses, the author proposes the following advantages of the stock market:

With an entire business, one has to run it or find someone who can. This requires an enormous amount of dedication to be successful.

In the stock market, one has to buy a business that is already staffed, yet will be entitled to share the earnings.

With whole businesses, the prices offered are not usually as attractive as they can be in the stock market.

Acquiring an entire business requires a large capital. However, in the stock market, one can start with just a small amount of investment and add to that capital over the years which is a great advantage.

The preference offered to buyers of private businesses does not correlate to that offered by the stock market. The investor has an alternative to purchase from 100,000 companies worldwide with a few brokerage accounts. On the other hand, investors can hardly find any private businesses for sale within a radius of 25-mile.

While purchasing a private business, transaction costs can add 5%-10% to the price. However, in the stock market, the frictional costs are extremely low even for an extraordinarily active investor.

The stock market offers the best possibility for achieving extraordinary returns on investment as long as investors follow the "Dhandho" approach.

Dhandho 102: Invest in Simple Businesses

Now that the author has affirmed that the stock market is the best place to look for returns, he discusses why their investments should be restricted to simple and predictable companies.

A stock will sell for a particular value in the market. The investors must compare this selling price to the actual worth of the underlying business. The worth of the underlying business is inferred based on its future cash inflows and outflows.

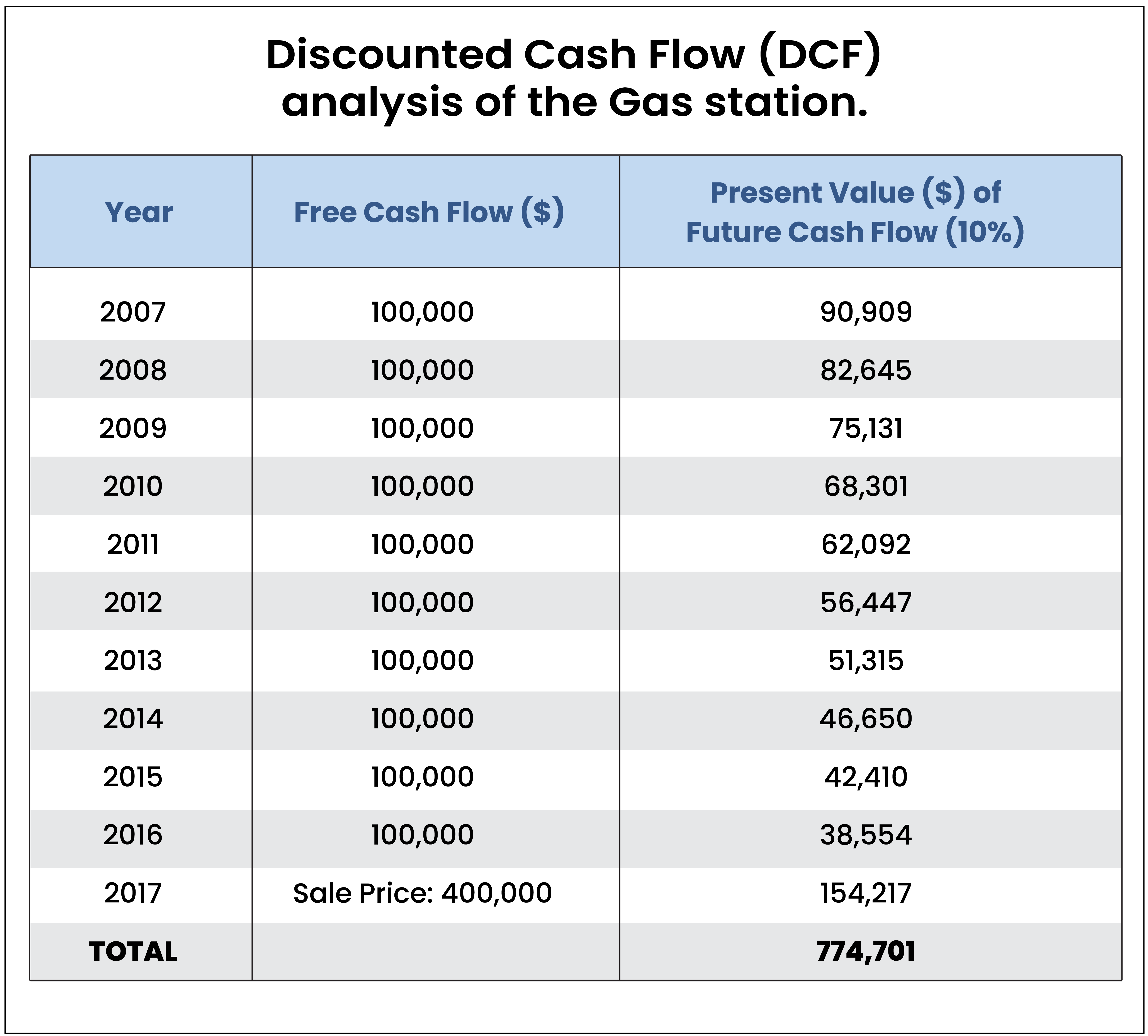

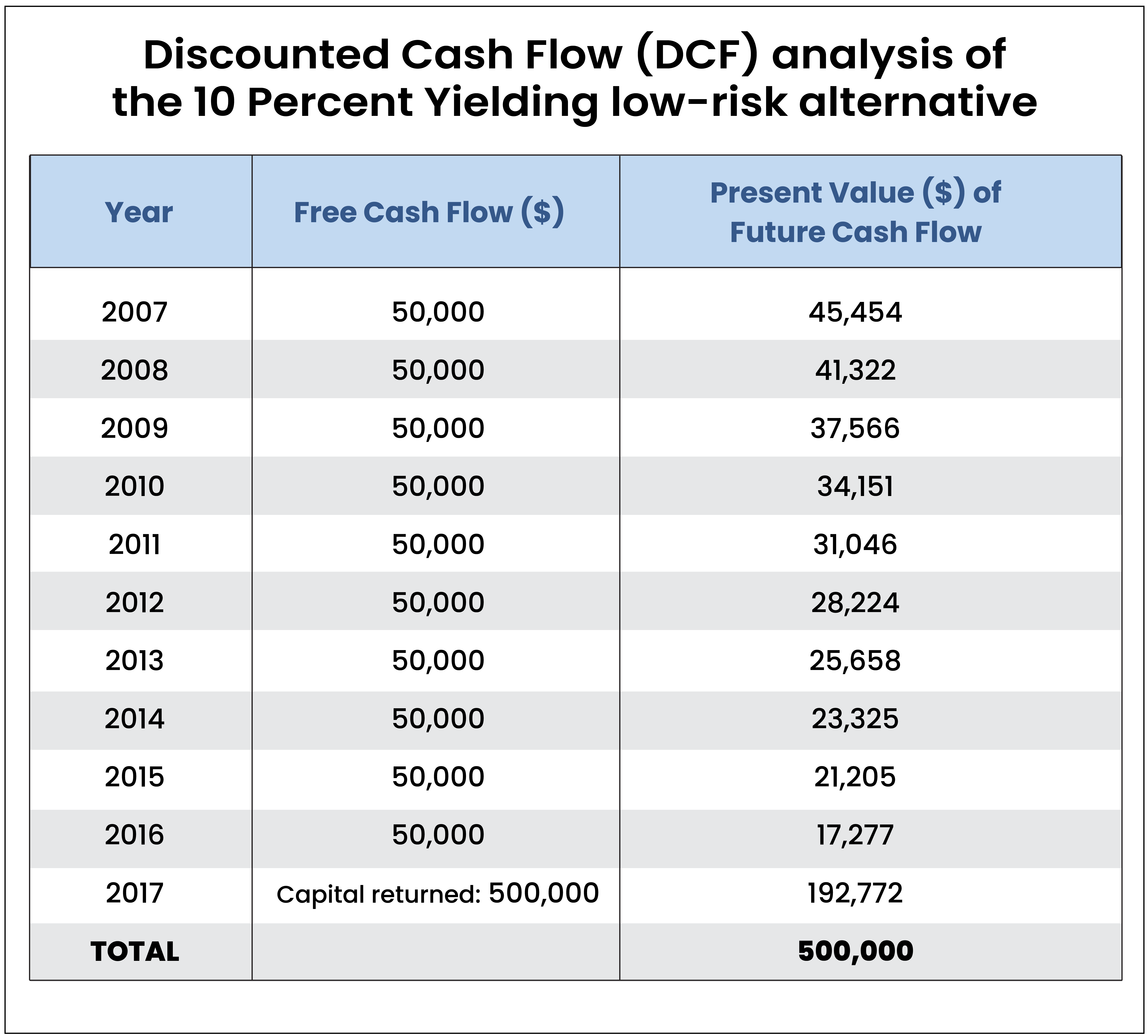

To validate this, the author cites an example of the gas station that was put up for sale at $500,000 at the end of 2006. Assuming that the gas station can be sold at $400,000 after 10 years and free cash flow expected per year is $100,000. Considering that we have an alternate low risk investment opportunity which can yield 10% annualized return. Which one should be a better alternative?

To decide, the author has used Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis. The table below shows how each year's cash flow has been discounted to its present value. According to this method, the intrinsic value of the gas station today is $7,75,000 approximately. However, we are buying it at $500,000 , which is just two-thirds of its intrinsic value.

Further, considering the alternative investment opportunity of 10% annualized return, its intrinsic value is exactly the same as the investment value, $500,000.

When there is a huge favourable gap between intrinsic value and the price of the investment, one must buy that business.

The author also takes a quick valuation of Bed, Bath and Beyond in 2006. While the stock sells with a market value of about $11 billion, the estimate of the company is probably worth between $8 billion and $20 billion. Hence, this investment should not amuse the investor much.

However, the valuation can change dramatically by changing the expected estimates of its cash inflows and outflows. Only because of this reason, it is extremely important to stick to simple and easy-to-understand business. If the future of a business can be predicted, its intrinsic value can be calculated more accurately. In turn, this enables the investor to recognize that he is buying a company at a discount.

Dhandho 201: Invest in Distressed Businesses in Distressed Industries

In this chapter, the author introduces the merits of investing in struggling businesses in struggling industries. While he imagines the market is generally efficient, he believes that investors can carefully find the situations where it is not. When a company or its industry is in trouble, it can often sell at a substantial discount to its intrinsic value due to widespread fear in the marketplace. It is this phenomenon that has created opportunities for investors to buy stocks at deep discounts.

For those who think that the market is always efficient, the author mentioned a few famous quotes by Warren Buffet in his book: "I'd be a bum on the street with a tin cup if the markets were always efficient."

"Investing in a market where people believe in efficiency is like playing bridge with someone who has been told it doesn't do any good to look at the cards."

"It has been helpful to me to have tens of thousands [of students] turned out of business schools taught that it didn't do any good to think."

Mohnish Pabrai, discusses several ways for investors to find struggling industries/companies. For one thing, corporate headlines are often filled with negative news and outlooks for specific companies and industries. Examples include Tyco's stock during the Kozlowski scandal, Martha Stewart's stock following her prison sentence and H&R Block's stock after Elliot Spitzer's investigations.

Another useful place to find trouble is Value Line's weekly report of the stocks that have lost the most value. It also releases a list of the stocks with the lowest P/E and P/B values. Pabrai also recommends reviewing 13-F disclosures to see what other investors are buying and using Value Investors Club. He also suggests that investors read Greenblatt's The Little Book That Beats The Market for assistance in this area.

From the above sources, it is possible to identify many troubled industries and companies. He recommends that investors exclude those businesses which are not simple to understand or fall outside the investor's competence. For the remaining stocks, the Dhandho framework should be pursued to determine which of these stocks should be bought.

Dhandho 202: Invest in Businesses with Durable Moats

In this chapter, the author suggests that because no moat can last forever, readers should invest in businesses with competitive advantages that last for many years. There is a vast list of businesses with durable moats like Coca-Cola, Chipotle, American Express, H&R Block, Harley-Davidson, Citigroup, BMW and WD-40.

There are also a few companies with no moat at all: Cooper Tires, Delta Airlines, General Motors, Encyclopedia Britannica and Gateway Computers.

At times the moat is not very clear. The instance of Tesoro Corporation, an oil refiner, is emphasized. Even though Tesoro has no control over the price of the crude oil supplies or the price of gasoline, its principal product, it does have an advantage over refineries on the west coast. Although the number of refineries has declined over the years, Tesoro holds an increasing advantage because of environmental regulations for gasoline products that are distinctive to the West Coast.

Even though a business' moat is usually hidden, whether a company has one is often clear from its financial statements. That is because good businesses produce high returns on invested capital. For instance, if starting a Chipotle store costs $700,000 while it generates $250,000 per year in free cash flow is an extremely good business according to the author.

While some moats are long-lasting than others (e.g. American Express was created 150 years ago but still has a strong moat.), it is important to notice that all moats erode over time. Even apparently unbeatable businesses today such as Google, eBay, Toyota, Microsoft and American Express will all ultimately decline and disappear.

The study of Arie de Geus showed that the average life of a Fortune 500 company is only 40 to 50 years, and it takes about 25 to 30 years from the origin for a particular company to get to the Fortune 500. This means the particular company doesn't exist after spending less than 20 years on the list. This implies that discounted cash flow measures into the future should be kept to rather short timeframes.

Dhandho 301: Few Bets, Big Bets, Infrequent Bets

The basic idea behind this chapter is that when an opportunity exists, it is important to bet big. The author is not an adviser on investing often, with money that won't move much. Instead, he suggests investing disproportionate amounts of money when the odds are clearly in his favour.

To compute how much an investor should bet on a given opportunity, Pabrai recommends using the Kelly Formula. It calculates the optimal fraction of bankroll to bet.

Edge/odds = Fraction of your bankroll you should bet each time

However, a major drawback of using this formula is that it requires knowing the payout amounts and the odds in advance. This information is available in gambling games (where the Kelly Formula is probably more applicable), but stock returns are not computed with so much assurance. To better understand how investors should think about investing in a particular opportunity and why, he proposes William Poundstone's book, Fortune Formula.

Although the motel-buying Patels depicted in earlier chapters of the book may have never heard of the Kelly Formula, Pabrai claims that they still recognize the basic concept behind it and that is why they were so successful: when a great opportunity arises, bet big. Pabrai also evaluates the statements and writings of Charlie Munger and Warren Buffett and concludes that they use the very same credo. Charlie Munger said in a speech at the USC business school:

"The wise ones bet heavily when the world offers them that opportunity. They bet big when they have the odds. And the rest of the time, they don’t. It’s just that simple."

And Warren Buffett wrote in his partnership letters from 1964 to 1967:

"We might invest up to 40% of our net worth in a single security under conditions coupling an extremely high probability that our facts and reasoning are correct with a very low probability that anything could change the underlying value of the investment."

As a result, Pabrai finds it confusing that the average mutual fund holds 77 positions and the top 10 holdings represent just 25% of assets. Dhandho, on the other hand, as he explains it, is about making small bets, big bets and occasional bets.

Dhandho 302: Fixate on Arbitrage

The author recommends investors to "fixate on arbitrage", especially in those situations where downside risk is eradicated, even if upside prospect is limited. He talks about the following types of arbitrage, with special emphasis on the last one:

- Traditional: Buying gold at a lower price on one exchange and selling it at a higher price on another.

- Correlated: Buying shares of a Class B stock while shorting the shares of Class A if there is a price/value disparity.

- Merger: Acquiring a company about to be bought out by another. It is crucial to note that this kind of arbitrage is normally not risk-free.

- Dhandho Arbitrage: It is the primary theme of this chapter. It allows businesses to earn above-normal profits for a restricted time before competitors and substitutes enter and demolish these higher returns. According to Buffett, a moat is a sustaining Dhandho arbitrage.

The author further explains the Dhandho arbitrage spreads of different businesses. Few have spreads of just a few months, while others have spreads that stretch for decades. While he asserts that the "Dhandho arbitrage spreads" of all businesses will ultimately be eroded, two vital factors can allow investors to earn outstanding returns in the interim: the most or the size of the spread, and its timespan.

In the end, he portrays a couple of businesses owned by Warren Buffett that don't have moats any longer, Blue Chip Stamps and World Book. However, the "arbitrage spread" obtained by these companies over the years has helped Buffett make a lot of money. For example, his purchase of See's Candy was partly bought by money reaped from Blue Chip. The author recommends investors looking for exceptional returns should invest in companies with wide and lasting Dhandho arbitrage spreads.

Dhandho 401: Margin of Safety—Always!

This chapter emphasises the significance of purchasing investments with a decent margin of safety only. He uses Buffett's quote to back up this point:

"Make sure that you are buying a business for way less than you think it is conservatively worth."

He also relates to Ben Graham's writing in the book ‘The Intelligent Investor’ by pointing out that Graham talked about the following joint benefits of utilizing a margin of safety: lower downside risk and greater upside potential.

The entrepreneurs depicted at the beginning of this book had likely never read Graham's writings. However, their decisions were always taken by keeping the idea of risk minimization in mind. On the other hand, Business schools do a great injustice to their students by teaching that reward comes from risk.

The impression that higher rewards can be gained through higher risk only is a common idea for those who think that the market is efficient. Hence it does no good to look for low-risk, high-reward situations. On this subject, the author once again quotes Buffett:

"We are enormously indebted to those academics: what could be more advantageous in an intellectual contest - whether it be a bridge, chess, or stock selection than to have opponents who have been taught that thinking is a waste of energy?"

Dhandho 402: Invest in Low-Risk, High-Uncertainty Businesses

The theme of this chapter is that high uncertainty does not mean high risk. Wall Street will often elude companies with uncertain prospects, but this is what allows value investors to jump in and earn excessive profits. The author takes the reader through three examples of Pabrai fund purchases and the excellent returns that were realized.

Stewart Enterprises, an over-leveraged funeral home operator, traded at a 50% discount to its actual book value. Wall Street penalized the stock because its debt was coming due; but according to the author’s estimation, the probabilities of bankruptcy were slim. The company had positive earnings and cash flows and consisted of several businesses. Stewart was able to sell off businesses that were not cash positive and consequently pay off its debt without harming cash flows.

Even though Level 3 Communication, a telecommunication giant had cash of $2.1 billion, some of the company's debt sold for 20 cents on the dollar due to the company’s negative cash flow and uncertain industry outlook. A thorough analysis of management's plans, however, indicated that capital expenditure would not be spent unless earnings justified expansion. This meant that the company's cash reserve could continue to cover interest payments for another three years. Due to the low bond prices, the investors could recover their initial investment in interest payments alone!

Frontline, a commodity shipping company, sold at a steep discount to the scrap value of its ships in 2002. In addition, Pabrai asserts it had adequate liquidity to last several months at the miserable shipping prices that persisted in the market at the time. Needless to say, the company outlived the downturn, and Pabrai was rewarded for his investment.

Although all of the above companies were in different industries and different circumstances, each investment symbolized an investment in a highly uncertain yet low-risk position. Because of Wall Street's resistance to high uncertainty, value investors can profit by discovering investments that fall within this group.

Dhandho 403: Invest in the Copycats rather than the Innovators

Many companies are committed to some sort of innovation, and many investors are looking for the next big innovation that will generate a superior return on investment. However, the author argues that instead of focusing on innovative companies, the investors should rather focus on companies that excel at copying and scaling.

He goes through a few case studies to illustrate his point. Ray Kroc purchased a McDonald's restaurant from two brothers. He didn't invent the concept but saw its potential and developed it. In addition, many of the menu items and processes that made McDonald's the restaurant we see now did not come from the company's headquarters but from its franchisees and other restaurants. McDonald's was successful because it was able to extend the innovations of others.

Microsoft is another company that the author describes as a non-innovator that excels at scaling up the successful innovations of others. Microsoft's inventions often fail, but it is when they take the existing ideas of their competitors and apply Microsoft's know-how that they are the most successful. It took the mouse and graphical user interface ideas from Apple, Excel from Lotus, Word from Word Perfect, networking from Novell, Internet Explorer from Netscape, XBOX from Playstation and the list goes on. In these cases, Microsoft waited for a certain product to illustrate customer acceptance and then went after the proven market.

Pabrai Funds is also a copy of Warren Buffett's funds to a wide degree. From the fee structure to the philosophy of identifying good investments to the reporting system, investor profiles, and staffing structure, Mohnish Pabrai has attempted to emulate Buffett's past partnership.

Too many investors make the mistake of looking for innovators in the stock market. Instead, Pabrai advises focusing on businesses run by people who have repeatedly shown they can enhance and expand on existing ideas.

Abhimanyu’s Dilemma—The Art of Selling

In the investment world, a lot is said about timing a stock purchase. In comparison, very little time is spent on selling. Indeed, the earlier chapters of this book have information about buying. This chapter discusses the process that investors should go through to decide whether or not to sell.

First, the author advises investors to have a selling plan for stock before buying. Once an investor has purchased without a plan, he will be subject to the psychological distress of stock ownership that may provoke irrational behaviour. A plan can help avoid a bad decision.

Once a stock is bought (probably at a discount to intrinsic value), he recommends holding it for at least two years. Although he admits that the number is rather arbitrary and that he has no empirical data to back it up, he argues that a few months is not enough for a company’s value to change considerably (the intrinsic value could not have decreased by such a large amount) and 5-6 years is too long to have money tied up because of opportunity costs. The only time Pabrai believes an investor should sell within two years:

1) The company's intrinsic value can be estimated over two years with a high degree of certainty

2) The price proposed is higher than that estimated value.

Note that in any such event, the future becomes uncertain after the stock purchase, Pabrai advises investors to hold (since rule 1 above is not met) because he believes the clouds of uncertainty tend to dissipate over several months. To demonstrate this point, he cites an example of a theoretical gas station whose future cash flows become uncertain, as well as a real example he experienced in his fund.

Furthermore, after three years, if the security fails to reach its intrinsic value, Pabrai argues that the investor is likely to miscalculate its valuation or that its intrinsic value may have declined. On the other hand, if the stock appreciates below 10% of its intrinsic value, he strongly recommends investors should consider selling. If a stock's price exceeds its intrinsic value, he recommends an immediate sale (with the sole exception of tax considerations, if necessary)

To Index or Not to Index—That Is the Question

Mohnish Pabrai concedes that the returns from investing in stock indexes will be better than the returns yielded by most active managers. In the aggregate, active managers are the market, and hence after incorporating frictional costs, active managers in the total will always underperform compared to the market.

However, he asserts that Dhandho investors will always outshine the market, and thus he suggests that individual investors, who don't have much time and inclination to invest in a Dhandho manner, should find such a manager.

For those who are interested in finding the investments themselves, he proposes ten places where "50 cent dollars" can be found, which means investments worth one dollar but are selling in the market for 50 cents:

- www.magicformulainvesting.com: Stocks are ranked by P/E ratio. Pabrai recommends this as an incredible screening process.

- The Value Investors Club website by Joel Greenblatt: It contains the stock ideas of other value investors.

- Subscribe to Value Line's bottom list: Stocks that have lost the most value in the last week, stocks with the lowest P/E ratio, etc.

- Look at the 52-week low lists on the NYSE daily

- Subscribe to Outstanding Investor Digest and Value Investor Insight: Both comprise interviews with great value investors who offer up some ideas every once in a while.

- Portfolio Reports: This edition lists the recent buying activity of some of North America's top money managers.

- Guru Focus: A site devoted to tracking the buying and selling of some of the world's top value investors.

- Super Investor Insight: Tracks the 13-F filings (a quarterly report that must be submitted by institutional investment managers to the SEC to disclose their investments) of the super investors.

- Major business publications like Wall Street Journal, BusinessWeek, Fortune, Forbes, etc.

- Attend the biannual Value Investing Congress

- By using the above resources, one is bound to find good ideas. The author asserts that these resources are invaluable, considering the value investor does not need many ideas to succeed.

Arjuna’s Focus: Investing Lessons from a Great Warrior

In the final chapter, the author begins with a fable that demonstrates the importance of concentrating on companies within one's circle of competence. Investors can pick and choose from thousands of companies (both private and public ), real estate, treasuries, currencies, options, mutual funds, hedge funds, commodities and other investments. If the investor tries his hands on all of them, he is unlikely to do well. However, the investor increases his odds by focusing on simple and understandable businesses.

He advises investors to look only for opportunities that fulfil this criterion. Once an opportunity arises, it should be studied, and examined closely and it should be made sure that it's trading at a discount. "Do not make the fatal mistake of looking at five businesses at once," he argues. One should rivet his eyes on one company at a time, and only after completing the analysis should he be ready to look at other companies within its circle of competence.

While the book attempts to educate readers on how to maximize their wealth, the author asserts that there is more to life than wealth. A life directed only on boosting material wealth is not fully rewarding. He concludes the book by persuading those who find success in Dhandho to invest in offering some of their wealth to those who are not so blessed.

Conclusion

This book starts with entrepreneurial applications of the Dhandho philosophy and later takes an investment angle. This interesting book is expertly written and the ideas can be used in any free market economy.

The clues to building wealth in investing or entrepreneurship are not very different. It involves doing a lot of legwork to spot the right opportunities, investing big (either in the form of money or time), being patient and realising great value when the right time comes.

The book ends up with two fables from Mahabharata. One about Abhimanyu to demonstrate how to get out of an investment and another about Arjuna about how to stay focused.