Introduction

About the book

This book 'The unusual billionaires' by Saurabh Mukherjea (author) gives you a perspective on how to identify great companies that are to be held forever. The author uses his coffee can screening mechanism and finds a list of 7 companies in the year 2016. Those companies were earning a ROCE higher than 15% and sales growth higher than 10% CAGR over the last ten years. These companies, on average, have delivered 28% CAGR over the last ten years compared to Sensex's CAGR of 14%. Through this book, he has identified three themes in the philosophy of the company/management that, according to him, are common traits for wealth creation:

- Focus on the long term without being distracted by short term gambles.

- Constantly deepen the moat around the core franchise

- Sensibly allocate capital whilst studiously avoiding betting the balance sheet on expensive and unrelated forays.

You need to concentrate on these themes while analysing a company, along with a checklist present at the end of the book summary.

About the author

Saurabh Mukherjea is a bestselling author and the founder and CIO of Marcellus Investment Managers. Previously, he was the CEO of Ambit Capital, an Indian investment bank. He was rated the leading equity strategist in India in polls conducted by Asiamoney in 2014, 2015 and 2016. A London School of Economics alumnus, Mukherjea, is also a CFA charter holder. He has authored five books till now.

Buy the book

The book teaches you how you can identify quality stocks for your investments that will help you generate enormous wealth over the long term. We highly recommend you to read the entire book.

Searching For Greatness

Saurabh Mukherjea has started the chapter with an interesting story of how he found one the best stock picks of his life, “Asian Paints” during a train journey. Unexpectedly, this story did not leave him with a specific answer, but a very important question, “What defines a great company.”

According to Mukherjea, Asian Paints was not making an exceptional product that was irreplaceable. Many companies were making high quality paints and some even at a cheaper price than Asian Paints, but still, the project consultants and painters still recommended the brand. So, what made this a great company? According to his research, a great company is one, which:

- Attracts best talent

- Commands respect in the business community

- Generally, trades at a premium valuation in the stock market

To him, stock prices are an “Effect” and not “a cause” of a company’s greatness. Investors reward the strategies that businesses have created to win their rivals. This was the reason why Asian Paints is called a "Great Company”. The massive dealer and distributor network, the company has created over years, pose a huge entry barrier for the competitors, apart from the premium quality product.

With this he moves his analysis to quantify the characteristics of quality companies so that investors can easily look for the important variables in the fundamentals of the company and identify the “Great company.” Therefore, with this section, he is helping us develop a stock screener.

Step 1

Define Companies: Out of all the stocks listed in the Indian stock market, Mukherjea has excluded companies with mcap lower than 100 crores which leaves him with about 1500 listed companies. From this universe he selects the stocks which possess quality factors.

Step 2

Define Long Periods: He has taken a time horizon of 10 years for his study. The logic behind this is that a decade usually covers a full business cycle.

Step 3

Define Superior Financial Performance: According to him, two major factors investors look for is a profitable company that is able to grow by reinvesting these profits. Therefore, his screen includes companies that have been able to deliver a 10% revenue growth and a 15% ROCE every year for the past ten years. Let's understand why this 10% revenue growth and 15% ROCE are important.

- India’s nominal GDP growth, which is the real GDP growth plus inflation, has been about 14.5% over the past ten years. And since India on average is growing by 14.5% annually, a company should at least grow at this rate if operating in India. However, to be conservative, he has considered 10% growth rate as a threshold.

- Now, why is 15% ROCE an important factor? According to Mukherjea’s study, the weighted average cost of capital, which is an average of cost of equity and cost of debt, for the Indian companies is about 15%. This means that for a company to actually create value, for both the equity and debt holders, it has to earn a rate of return higher than 15%. Companies with high ROCE have been able to beat the market index (BSE200) by an impressive margin.

The author has clarified that he is not looking for companies with just the highest revenue growth or the highest ROCE. He likes consistency and hence has based the rule that his selection companies must be generating at least 10% sales growth along with at least 15% ROCE for the past ten years. This shows their capabilities through both good and bad times.

As simple as the screen looks, as difficult it is to achieve this. In fact, for the ten-year period spanning FY06 to FY15, out of 36 companies growing revenue at a rate higher than 10% and 102 companies generating ROCE above the threshold of 15%, just 18 companies were able to satisfy both criteria over the decade.

For financial services firms such as banks, NBFCs, etc. Mukherjea has taken separate factors that include a 15% ROE and loan growth rate of at least 15% over the ten-year period. The logic for these numbers were quite similar to the ones used in the initial screen.

Asian Paints: Seven Decades Of Excellence

The chapter starts with the history of the paint industry in India. During World War II, there was a ban of imports on paint. This gave domestic entrepreneurs to take a look at this industry which was earlier dominated by a few MNCs and few Indian companies like Shalimar.

Asian Paints was started around that time by a twenty-six-year-old entrepreneur, Champaklal H. Choksey and three of his friends – Chimanlal N. Choksi, Suryakant C. Dani and Arvind R. Vakil. After Champaklal’s death, his family sold their stake and now the three families own majority stake in the company. According to Mukherjea, Asian Paints is an exemplary case study of a home grown brand taking on domestic and foreign competition and winning in India. The company, also being majorly held by promoters, is professionally managed. A trait less seen in the Indian context.

Mukherjea has divided the company’s journey into 3 phases over the years. Each phase led to a transformation in the company to make it stronger for the future. Let’s look at each of the stages.

Phase 1: 1942-67

The company started in 1942 by the four friends. Out of them, Champaklal is remembered as a visionary and a statesman to the paint industry. His strengths lay in reckoning the consumption trends and patterns earlier than the competition. He also recognized early that industrial paints were not a segment to concentrate upon due to lower margins. He instead bet his fortune in developing the decorative paint market in India. Contrary to the expectations, he actually started from the rural markets.

The company began by pitching its paints to Tamilians during the Pongal festival and Maharashtrians during the Pola festival. Here, people used paints in order to paint bulls’ horns which were worshiped during the festival. Here Choksey noticed that small packs of good quality paints were not available. Hence, he started to market small packs of these paints even at low margins to gain customer trust. Now as the company gained popularity, even the city dealers wanted to stock the company’s products.

The next consumer demand gap was noticed by him when he saw that plastic emulsion paint was 5 times costlier than basic distemper. People hated basic distemper as the quality was not good, however, were left with no choice due to unaffordability. Hence 1950, he introduced washable distemper placed between dry distemper and plastic emulsion.

By 1967, by its twenty fifth year, the company became the largest paint company in India by revenue. The company was also able to improve its margins and return ratios by the end of this phase.

Phase 2: 1967-97

The company also understood quite early that it needs to hire best in class talent and retain them for long, if they wanted to succeed in the ever-changing market. Asian Paints recruited from top Indian institutes like IIMs, IITs, etc.

The company was also far sighted enough to understand the importance of computers and hence became the first Indian company to purchase a mainframe computer back in early 1970s. The company used to forecast demand in order to improve supply chain efficiency. In 1982, the company got listed on the stock exchanges to create history. The company has given a CAGR of 25% from 1991 to 2016. If you had invested ₹ 1 in the shares of Asian Pains in Jan of 1991, it would be worth ₹ 299 by April 2016. Compared to this, a rupee invested in Sensex would be worth just ₹26.

This phase also saw the rise of Atul Choksey, son of Champaklal Chowksey. Like father, he also went ahead with strengthening the operating efficiency. He was credited with expanding the operations of the company beyond west India, to south and north. Many iconic Asian Paint’s brands like Utsav and Royale were launched. The quest for expansion continued with entering into joint ventures (JVs) for manufacturing automotive finishes and certain industrial products.

Hence Phase 2 saw the expansion of the company along with investment in IT infrastructure.

Phase 3: 1997-2015

This phase started with the loss of Champaklal Choksey, who died at age of 81. After this, there were a few instabilities in the relationship of the promoter families. Atul’s plans were not being approved by the other three families and hence out of anguish, Atul sold 9% of his stake to a competitor. However, this sale was blocked by the promoters and finally after an eight-month long battle, the competitor had to sell that stake to some mutual funds.

After this, the remaining three families thought of modernizing the structure of the company. They hired management consultants who advised them on best manufacturing practices, improving working capital cycles, improving organizational structure, etc. By 1999, the company started aggressively investing in technology such as software for supply chain and demand forecasting and ERP. This resulted in an impressive reduction in the working capital days of the company from 100 in 1995 to just 20 in 2015.

During this phase, the company also expanded to Oman, Sri Lanka, Egypt and Singapore. They entered into the Home Improvement Division in 2013.

To summarize, in Phase 3, the company got institutionalized by being managed professionally, i.e., by a non-promoter CEO. In addition, technology enabled the company to drastically reduce management’s efforts in day-to-day operations and concentrate on expansion. Home Improvement Division like Modular Kitchens and Bathroom Fittings, were possible due to this increased bandwidth.

Now, what is the secret sauce of Asian Paints success?

Well, there can be many, but the author has left us with 2 main factors.

- Focusing on Core Business: Throughout the first 50-60 years of inception, the management had spent their time and money on just two things, supply chain efficiency and brand development. This paid off well in the future. The promoters refrained by going into unrelated diversifications.

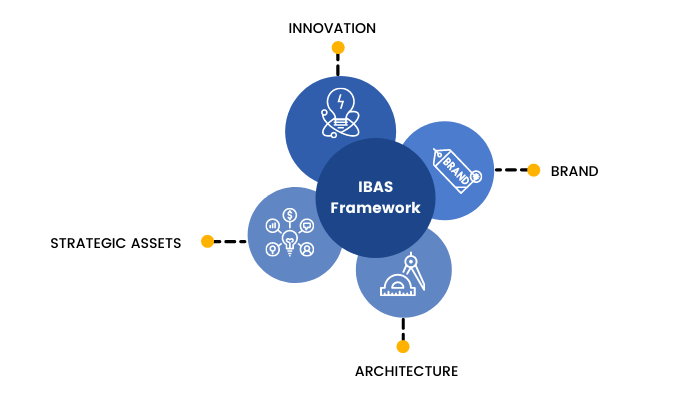

- Deepening Competitive Moats: We understand this by Mukherjea’s IBAS framework - Innovation , Brand , Architecture ,St rategic asset.

Innovation

- Product innovation: Starting right from the beginning, the company came up with small packaging of paints that can be used during festivities. Then washable distemper was a successful innovation.

- Supply chain management: Asian paints was the first one to give its distributors a 3.5% extra discount if they made payment on time. Then they used GPS to track their goods in transit. Demand forecasting and electronic billing at the branch level were also some of the supply chain innovations that made the company a success.

- Empowerment of professionals: The promoters are credited to have kept a culture in the company that ensured quicker decision making with biases or interference from the promoters. Hence, they were able to attract and retain talent even with a lower base package than the industry.

Brand

The company has a very strong brand recall. They have spent heavily on advertisements. The “Gattu” mascot was designed by the famous RK Lakshman and remains the longest run mascot for the company as it attracted the Indian consumers. Post 2002, the company moved towards premium marketing.

Architecture

There were three critical aspects of Asian Paints architecture:

- Creating a unique working culture that nurtures talent.

- Using technology to improve competitive advantage.

- Creating an independent board of directors to shape the evolution of the firm.

Strategic Asset

The company’s strategic assets are:

- Its wide geographical spread of supply chain network

- Deep rooted relation with paint dealers

Mukherjea also notes that it seems that now the company is preparing for the future by investing in:-

- Business related to homes such as kitchenware and bathroom fittings

- Services they could disrupt the traditional Indian model of hiring painters to paint their homes.

Berger Paints: 250 Years In The Making

The chapter begins with an interesting history of Berger Paints, which very few of us were aware of. Berger Paints was established in the year 1760 by Lewis Steinberger. Since then, the company has changed hands thrice till it came to the hands of Vittal Mallya, the father of liquor baron Vijay Mallya. Vijay Mallya, after the death of his father, acquired the overseas operations of Berger Paints, except Australia, Europe and UK. The final take over of the company’s ownership happened in 1991, when Mallya sold the stake of Berger Paints to the Dhingra brothers, namely, Kuldip Singh and Gurbachan Singh.

The author has divided Berger Paints corporate story into three phases.

Phase 1: 1972-91

As many of you might be aware, in the Indian FMCG industry, HUL is considered the CEO factory. This means, many of the HUL employees have gone ahead and become successful CEOs of other FMCG companies. The HUL of the paints industry is Asian Paints. Many Asian Paints’ employees went on to lead other paint companies and changed their fortune. The case of Berger Paints was no different. Berger Paints of today would be a lot different if Biji Kurien did not join the company from Asian Paints in 1972. Kurien is titled with two major achievements at Berger Paints. They are:

(a) Changing the work culture at the firm.

(b) Shifting the focus towards decorative paints from industrial paints.

Kurien hired high quality talent and encouraged a culture to give full autonomy to employees.

For developing the decorative paints division, the company hired the Lintas Media Group, which at that time was India’s largest advertising agency. Berger also pioneered the concept of contract manufacturing to improve operating efficiencies. Also, during this era (1972-91), supply chain efficiency, productivity and operational excellence were initiated. These strategies led Berger Paints to gain market share and become the fourth largest player by 1980.

This phase ended with the change of ownership from Mallya’s UB group to the Dhingra family. The Dhingra family was already running a paints business where they majorly exported to Russia. They thought acquiring Berger Paint’s global business was a strategic fit.

Phase 2: 1992-2010

Unlike Asian Paints, the expansion into the decorative segment had dented Bergen Paints balance sheet. This was the likely reason for the sale by UB group to the Dhingra family. There were working capital issues and delays in salaries to the employees. The company had just one manufacturing unit in (1992), from where they used to cater to the whole of India and subsequently faced supply chain issues as demand rose. However, Kuldeep Singh Dhingra is said to be confident of Kurien’s capabilities and hence retained him. He also identified liquidity bottlenecks and pumped funds into the company through short term loans, convertible debentures and preference issues to help unleash Berger’s potential.

The company stepped into another innovation with the launch of color tinting machines, thereby increasing color shades from just 125 to 5000+.

By 1990, Berger became the number 3 player in both the decorative and industrial paints market.

Post Kurien’s retirement in 1994, the company was led by Subir Bose who had a decade long association with Berger already. He is said to lead the transformation of the company from industrial segment to decorative segment. Bose, also ramped up the rural presence of the company.

In order to solve the supply chain issues, Bose supplied a tinting system to more than 1000 outlets and also acquired manufacturing units in Nepal.

Phase 3: 2011-15

This phase, according to the author, began with the appointment of Abhijit Roy. Coincidently, the change in management also saw the rise in Berger’s revenue growth relative to the market leader, Asian Paints.

Roy had spent 16 years with the company at different capacities. Under Roy, Berger was able to raise the aspirational value of Berger’s brands, improved internal inefficiencies using IT, increased advertising spends, among others. These were combined with a constant cost reduction, increasing operating margins.

Among the notable improvements, were the rising gross margins of the company during FY10-15, by 450bps. This rise was despite no significant input cost reductions over the period. This was also not an industry-wide factor, as even Asian Paints margins were quite stable during this period. The author also noted that contrary to the belief that premiumization raised the gross margins, it was actually higher volumes with increased economies of scale that actually helped the company reduce the cost of goods sold. Efficient working capital management also contributed to the margin rise.

Let us now look at the IBAS framework to understand the competitive moats of the company post Dhingra’s acquisition.

Innovation

According to Mukherjea’s, Berger Paints’ innovations were across three fronts:

1. How promoters managed the firm.

Dhingra's, although one of the richest families in India, maintained a low profile with rare press interviews. The author also notes that his personal encounters with the Dhingra brothers left him with the notion that they were very grounded. Like Asian Paints, Berger is also professionally run, with little interference by the promoters.

2. Introduction of tinting machine to the dealers

For paint dealers, tinting machines did away with the need to stock a large number of SKUs. This reduced the space requirements and improved inventory management. During the 1990s, one tainting machine cost INR 8,31,000. This was a very high price of any dealer to pay upfront. However, with aggressive marketing, Berger was able to sell this to the dealers as a cost saving and space saving device. This was to that extent, whereby during 1999, 33% of the tainting machines in India were with Berger’s dealer network.

3. Introduction of innovative products

Berger has made sure that each of its products have some or the other special characteristics which have allowed it to create and sustain competitive positioning in the country.

Brand and Reputation

Berger has been able to create a strong brand in both the economy and premium segment. Berger’s advertisements were quite different from what was prevalent during those times. Some of them like “When the Piano is Steinway, the walls are Luxol Silk”, “Luxol Silk – the only emulsion paint you can tell with closed eyes”, etc. tried to enforce in the minds of people that Luxol was the brand that every premium household should have and can even increase the value of your expensive home accessories like Piano, Moghul miniatures, etc. Advertising spends actually took off for the company with the appointment of Abhijit Roy as CEO. They started spending about 6.6% of sales on advertising, higher than Asian Paints (5.2%).

Architecture

Berger has been able to recruit and retain great talent for a long time. Kurien used to say to the hiring manager, “Don’t recruit someone who is not able to do a job, just to fill a vacancy. Secondly, even if we don’t have a job, but you come across the right person, you must recruit him.”

The kind of autonomy that employees used to get at Berger paints, led them to attract talent even at a lower pay.

Strategic Asset

An all-India network of plants, manufacturing facilities and dealer-distributor network are the key strategic assets that build competitive moats around Berger Paints.

Marico: From A Commodity Trader To An FMCG Giant

Like previous chapters, this chapter too starts with an interesting story about how the company Marico got its name. It was actually named after the profession of Harsh Mariwala’s grandfather, Vallabhdas Vasanji who used to trade in pepper. In Gujarati, pepper is called Mari and Mariwala is a person who sells or trades spices. This made their family name Mariwala.

However, Marico as we know it today, was a lot different in its history. It was a family-owned commodity trading company called Bombay Oil Industries Limited (BOIL). BOIL was formed in the year 1948 and used to initially trade in spices and then began manufacturing coconut oil, vegetable oil and Chemicals. This remained a B2B company, until the legendary entrepreneur, Harsh Mariwala joined the family business in 1971.

This chapter of the book is divided into various phases., Let’s discuss each of them briefly to understand how the company took the current form.

Phase 1: 1972-91

While the family business (owned by four brothers) was running well, however, it remained a B2B. Harsh Mariwala was very keen on taking the business from a low margin one to a higher margin B2C which was more sustainable and profitable according to him. So, with the approval of other family members, Harsh started packaging the coconut oils in smaller 100ml packs. He also took other crucial areas like advertising, marketing, human resources and distribution.

Thus began the journey of building one of India’s most valuable FMCG multinationals. Harsh hired talents from other corporates and B-Schools. Among the first one was Bindumadhavan, a Ranbaxy veteran. He was a packaging expert and under his leadership, Parachute oil shifted from tin packaging to plastic bottles.

For Suffola, as it was a niche brand in Mumbai, but was not functioning up to its potential. It was showcased in research that sunflower oil reduced cholesterol levels. Hence it lit up Harsh to advertise Saffola brand on the health platform. Hence, he differentiated it from the regular cooking oil and was able to sell it at a higher price. By 1991, Marico became the market leader in edible oil.

Even after all these successes, the consumer division headed by Harsh became the main profit generator for BOIL but it still remained a part of the bigger organization and hence the chain of commands was extended. Therefore, in 1981, Harsh had suggested the creation of three profit centers – consumer products for himself, fatty acids and chemicals and spice extracts division for his cousins. However, even after this restructuring, Harsh’s consumer division was capital starved as it was hungry for growth. By the end of this phase, Harsh was clear to get the consumer division spun off the holding company BOIL.

Phase 2: 1990-96

This phase started with the spin-off of the consumer division of BOIL. However, the journey was not smooth. The separated entity with 80cr of capital was left with just 90 Lakhs of capital, 2.4 crores of reserves and 4.7 crores of debt. This led Mariwala to keep his focus on making an organization an attractive place for the best of management talent. Also, he decided to slow down the acquisitions.

Marico was amongst the first organizations in India at that time to have an open office. The company also revamped and expanded the manufacturing facilities. Marico was also the first consumer sector company that offered foreign trips to the distributors who achieved stretched targets.

The supply chain was also made more efficient with time. During this phase, Marico also started to expand internationally. According to Harsh, this encouraged managers to work as they were now able to explore multiple geographies rather than just India.

Phase 3: 1997-2006

In my opinion this was a phase which engraved Marico’s name in the Indian FMCG market. Even Mukherjea has kept his tongue in cheek while mentioning about the title of this phase, “David (Marico) vs Goliath (HUL)."

The battle of coconut oil became intense between Marico (which owns Parachute oil brand) and HUL (which owned the Nihar Coconut Oil brand). The battle started when Mariwala quite courageously dismissed HUL’s offer to acquire the Parachute brand. As we all know, Marico even at that time was a very small company in front of HUL. HUL had immense resources and foreign backing that made it spend aggressively on marketing in order to just win the war. However, for Marico, the stake here was survival. This gave the team enough motivation and they called this battle as operation “Parachute ki Kasam”. The company increased distribution, quality, etc. to sustain in the market.

The battle was finally won in 2005 when Nihar was put up for sale and Marico acquired the brand in 2005. This not only made the Parachute brand superior but also gave it pricing power and hence increased the overall margins of the company. After this, Marico acquired the Mediker brand and also launched Kaya skin clinic.

Mukherjea also notices that during this phase, Marico strengthened the internal processes and integrated the HR strategy with the overall business strategy. IT and supply chain management were also key focus areas during this time period.

Phase 4: 2007-12

In the earlier phases, Marico had focused on making itself strong internally. Now, the inorganic growth stage starts.

With the pilot project in Bangladesh being successful with Marico gaining 67% market share of coconut oil, they started acquiring other consumer brands in the emerging market region.

Some of the low margin products from the India portfolio were also dropped. In 2012, they acquired Paras’s personal care brands and entered into a niche market of men’s grooming.

Phase 5: 2013 onwards

As we know, acquisitions are capital intensive and so Marico’s ROCE during the phase 4 dropped significantly from 50% in FY08 to 24% in FY13.

But the company recognized this and Harsh Mariwala himself told in an interview that the company will now focus on digesting the earlier acquisitions and also try and raise the dividend payout to match other FMCG companies. Other corporate restrictions were carried out like demerger of Kaya clinics and appointment of Saugata Gupta as Marico’s CEO and subsequently Managing Director.

Mukherjea notes the secrets behind Marico’s success in the following sections

Section 1: Focus on Core Business

The company remained focused on maintaining brand leadership, extending winning brands and divesting low margin brands.

Section 2: Deepening Competitive Moats

This section was tackled through the IBAS framework. Let’s briefly look at each of them.

Innovation

Marico innovated in several areas like:

- Packaging: The shift from tin packaging to plastic bottles led to the oil becoming storable at the depots and offered protection from rats.

- Products: Through all its brands, Marico has positioned itself very differently in markets that were earlier unheard of. Some of these would be premium edible oil, male grooming, flavored oats, etc.

- Human Resource: Marico’s HR department is said to introduce various activities to keep the employees engaged and discourage unionization.

- Financial: Better budgeting of advertising spends, reserves for unexpected cost rise and demand forecasting kept Marico’s financials under check.

Brand

Marico remains a leader in the coconut oil market under the Parachute oil brand, under the premium edible oil market with Saffola brand and in the male grooming market with brands such as Set Wet and Zatak.

Architecture

The work culture at Marico can be compared to any other MNCs operating in India and abroad. Open office culture was introduced to corporate India by Marico. Also, the managers were given appropriate freedom and the company was run professionally as the promoters took a back seat and talented outsiders were allowed to take the company’s ambitions forward. The board of directors were also well diversified in terms of experience and expertise.

Strategic Assets

The network of distributors remains a strategic asset for the company.

Section 3: Controlled Capital Allocation

The company was able to generate higher capital because of

- Low capital intensity

- Low working capital requirements

- Higher operating profit margins

This allowed the company to increase its dividend payout ratio, acquire great brands or create brands internally.

Case Study: Page Industries

Like all the other chapters, Mukherjea has once again not failed to capture the interest of the readers through a brief yet interesting story of the company Page Industries.

For Page Industries, the roots went back to the Philippines during the time of World War II. During this time, V. Lilaram & Co. (led by Genomals) is used to import garments from neighboring countries and sell them to the Japanese and American Forces in Manila, the capital of Philippines. The most popular among them was undergarments by Jockey Inc. Soon, Jockey became popular with the local population in the Philippines. Seeing these developments, Jockey International gave exclusive license to the Genomals to form a company and launch the brand in India. Thus, forming Page Industries. Interesting fact, the company’s name Page Industries was derived from the initials of the name of promoter’s mother Parpati Genomal.

Let’s now understand the company better, by dividing it into Phases.

Phase 1: 1959-92

As described earlier, Genomals used to purchase and sell Jockey products in the Philippines. This led to the company providing them manufacturing rights for the Philippines in 1959. Since, the company was a licensee of Jockey International, this meant that it had access to all the innovations the company did sitting in the US. Jockey International was amongst the first companies in the world to display underwear prominently on shop floors, designed men’s briefs, stitching brand name on the waistband, bikini briefs for men, etc. These all had a role to play in expanding Genomal’s business in the Philippines.

To the credit of Genomals, they experimented with the concession model of retailing which is shop-in shop model, which allowed the brand to have a separate identity in the stores in the Philippines.

Now, the author moves to India, and tells us that Jockey did not initiate its Indian journey with Genomals. Instead, they first entered India in 1962 with Associated Apparels. However, due to unfavorable foreign policies of the Indian government during that time, the company decided to move out in the tenth year itself. This gave competitors like VIP, Rupa, Liberty, etc. to flourish in the absence of Jockey.

Jockey re-entered India only post 1991 liberalization.

Phase 2: 1993-97

Even though Genomals had clarified that they had never lived in India or done business here, Jockey International was keen to work with them since they trusted them and shared similar visions and values. The then President of Jockey International, Rick Hosley, rightly predicted that Genomals will lead that biggest licensee of Jockey in the world.

Before starting the operations, Genomal toured India in 1993 and researched about the undergarments market with the help of market research firm MARG. The response was positive and encouraging. Thus, Page Industries was incorporated in 1994 and set up the manufacturing plant in Bengaluru.

The promoters took a differentiated route on the distribution front. Rather than going after wholesale distributors, they chose individual distributors as they wanted to regulate the sales channel. Their products marketed at the shop as exclusive display fixtures and bold in-store marketing were also new to the Indian markets.

Between 1995 and 1997, Genomal built his core team to scale up execution. Pius Thomas, from telecom operator BPL, joined the company to look after finance. Shekhar Tiwari joined from Eureka Forbes to take charge of marketing and sales, and Vedji Ticku, also from Eureka Forbes, joined in 1997 as sales manager for the south zone. Thomas went on to become the CFO in 2012, while Ticku took over as CEO in 2016.

Phase 3: 1997-2003

Like all new entrants, Page too had its own issues. The major one of those was establishing relationships with high quality raw material suppliers. The high cost of advertisement too remained a concern as the competition was cut throat on margins.

But, it seems the luck was in favor of Page Industries. In 1997, TTK Tantex and in 2002 Associated Apparel fell prey to labor strikes and both exited the innerwear market, clearing northern and western India market for Jockey.

In the next three years, Page doubled its sales with a retail network of 10,000 outlets. Now, once established, it was now time for them to gain market share.

Phase 4: 2004-15

In these 11 years (2004 to 2015), Page’s revenues grew at an impressive CAGR of 35%. The major driver to this revenue growth was the launch of at least one new product every year. During this period, the efficiency of the company as measured by the sales per employee matrix also improved consistently as the company focused on automation, technology and data analytics.

What also led to the company's high growth during this period was focused advertising. This also made the company stand out from the new foreign brands that entered India during this period like UCB, Fruit of Loom, Calvin Klein, etc.

During this period, the company also entered the UAE market and signed one more license agreement with Speedo International.

Let us now come to the ending section of this chapter and find out the secret sauce of Page Industries that makes it so successful.

1. Focus on core business: Genomals have restricted themselves from unnecessary diversifications and remained committed to their business of innerwear. This led them to gain a 20-year extension of their license in 2010 compared to a normal practice of 5-year extensions by Jockey International.

2. Deepening Competitive Moats: Mukherjea uses the IBAS framework for this.

Innovation

The pace of new launches, quality and innovations in the products have kept the page ahead of its competitors. Representatives from Page Industries, Jockey USA and Jockey’s other licensees in different countries meet twice a year to discuss technology related to product development. Page itself has a 20 member R&D team to focus on innovations. Some unique strategies used by Page are free lunch to its workers, making its own elastic, both of these are uncommon in the garment industry.

Brand

Page Industries has well succeeded in maintaining the aspirational value of the brand Jockey over a long period of time. They are very conscious of the price point of the customers and do allow massive discounts by the retailers. Even the unsold inventory is sold by Page at a discount not higher than 40% in the second’s market. They consistently spend 5% of their sales on advertisements.

Architecture

Page’s strong relation with the labor force stands as a huge competitive advantage. They also try to empower the subordinates to bring out the best out of the team.

Strategic Asset

Mukherjea regards Page’s relation with Jockey as its biggest strategic asset. For Jockey, Page is the biggest franchisee.

3. Capital Allocation

The company is very strict with respect to the capital allocation and does not invest in projects that are non-core to the existing businesses. Also, the management has kept a threshold of 20% ROCE in order to undertake any new project. The company is not averse to borrowing, however, they have an internal policy to keep the D/E ratio at 1:2 or 50% with repayment of borrowing within five years. The company has also maintained a high dividend payout ratio of 50%+.

Case Study: Axis Bank

The author has started the chapter by explaining to us about the banking business. He says that the banking biz is different from manufacturing as the raw material and finished product for a bank is the same, money! There is no value addition done by the bank unlike a manufacturing company. Therefore, in banking the people who run the bank are considered the most important. As Warren Buffet quotes, “Banking is a good business if you don’t do anything dumb”.

Axis Bank as we know it today, started as UTI bank promoted by the Unit Trust of India in the year 1994. Axis Bank remains a case of losing many battles but winning the war. Let’s see the journey of the bank through three phases.

Phase 1: 1994-99

The Indian banking sector opened to the private players post 1994 when RBI issued banking licenses to ten private sector banks. Four of these were backed by large financial institutions such as HDFC Bank, ICICI Bank, UTI Bank and IDBI Bank. Five were backed by individuals and corporate groups: Bank of Punjab, Centurion Bank, Global Trust Bank, IndusInd Bank and Times Bank. There was also one cooperative bank that got converted into a commercial bank, Development Credit Bank (DCB).

Amongst them, the UTI bank, although given the stature of a private bank, was backed by government owned UTI. For those who do not know the history of UTI, until 1963, UTI was the only mutual fund available to an Indian investor. This gave UTI bank (now Axis Bank) a huge competitive advantage.

The strategy was to use UTI’s 35 million customer base to pitch the bank’s products. The dependence of the bank on UTI was immense. The bank was not even required to open branches and had just 7 branches in the first year of operation. It could operate directly from the 41 UTI offices over its first 5 years. The other advantage was tapping corporate clients of UTI to pitch the banking products.

The initial phase of the bank was led by a State Bank of India veteran, Supriya Gupta. Supriya had a good reputation amongst the banking community and was a member of the prestigious Bengal Club of Bankers. He was adamant in acquiring bank staff on personal relations rather than top IIT, IIM graduates. This although was not seen with much appreciation, however, some of his recruits were quite instrumental in the development of the bank. When recruiting on personal relation also meant that salary was not the deciding point of recruitment, but relations.

Like other startups, the culture at Axis bank, (then UTI bank) was very vibrant. However, the bank was not managed in the most ideal way possible and hence by the year 2000, the bank’s Non-Performing Assets (NPA) were the highest among the private sector banks. Till now, the bank was also not very successful in building the liabilities, which in the bank’s case are the deposit base.

Phase 2: 2000-09

The author has made a very important revelation here. He has told us that banking is a commodity business. Hence a bank needs to be a low-cost producer, i.e., a low-cost lender in order to thrive. In the present world, being low cost is possible only when a bank has low-cost liabilities called Current Account and Savings Account, called CASA in banking terminology.

This was well understood by the second lead at Axis Bank (UTI Bank then), P. Jayendra Nayak. Axis Bank as we know it today has been a baby child of the vision of Nayak. Ironically, he was a banker with no banking experience. He was a civil servant at the Ministry of Finance. He was the one who fought with the board of directors for getting the employee’s salary at par with the other private sector banks of similar size like HDFC and ICICI. ESOPs were also introduced during his early years.

Now, with making the employees happy, the next obvious step was to make customers happy. Hence, Nayak took the decision of being aggressive on branch and ATM expansion. This was possible as Nayak had convinced the board to get foreign capital of INR 157.5 crores from Actis Capital and South Asia Regional Fund. Axis Bank CASA thereby improved during this phase from 15% in FY01 to 44% in FY09, which compared well with others like HDFC Bank and ICICI Bank.

In 2007, With good capital, lower NPAs, high CASA, the bank was well positioned in itself and now was the time to leave the UTI image and build a new brand. Hence the bank was renamed “Axis Bank”.

Although Nayak's tenure was an immense success for the bank, the end was downhearted for him. Due to his unhealthy relationship with the board, the board had not allowed him to choose his successor and had instead bought Shikha Sharma from ICICI Prudential.

Phase 3: 2009-Present

Shikha, although not chosen by Nayak, had a very successful tenure. An IIM-A alumnus, started her career with ICICI Bank, spent three decades establishing the stock broking business at ICICI and lastly headed ICICI Prudential Life Insurance as the MD and CEO. Although she was not welcomed at Axis Bank due to Nayak’s denial and being from a competitor bank, she found her way out. As one of her first decisions, she decided to create four strategic units for the bank.

- Retail, SME and agriculture banking

- Corporate Banking

- Non-Banking Retail

- Corporate Center

She also hired a lot of new talent. Out of those, one out of box hiring was Mansha Lath Gupta from Colgate Palmolive. She was recruited as the Chief Marketing Officer to lead the bank's brand and communication strategy.

One controversial decision was acquisition of Enam Securities in the year 2010 for INR 2,000 crore. This made Axis compete with ICICI Bank on the investment banking and stock broking front.

In less than two years, Sharma changed Axis Bank’s team and operational structure, and completed a substantial acquisition. Her next move was to organize the loan book towards retail and reduce the concentration on corporate lending. Her approach towards retail built upon Nayak’s work. While Nayak successfully set up a large branch network and a proportionately large customer base, she used the same base to extend more retail loans and retail term deposits. Every customer who walks into a bank branch to open a savings account is also a potential client for a term deposit, credit card, personal loan and vehicle loan. A lot of data driven analytics was also used to drive retail lending in the bank.

Other notable offerings in her tenure were private banking for affluent customers, international banking, etc. all of which led to significant fee income generation for the bank.

IBAS Framework:

Innovation

The bank innovated the product profile catering to different segments of the society. The bank was also very aggressive in expanding the branch and ATMs across the country since Nayak took over. Another great move was to provide INR 2,00,000 of accidental insurance to a salary account holder hence relieving the employer of providing insurance separately.

Brand

The bank in its initial days had leveraged the brand image of UTI. However, since UTI was bailed out by the government for alleged security fraud and losing market share to the competitors it was strategically prudent to change the brand name to Axis Bank.

Shikha Sharma was also keen to make the bank a brand among the youth. Hence, she took the decision to get Deepika Padukone as the brand ambassador for the bank.

Architecture

The board of directors at Axis Bank were independent as shown during Nayak's fiasco when he was not allowed to keep his intended successor. The bank was also very employee friendly and the culture helped in retaining talent. This is evident from many employees having a four-digit employee code that were issued when the bank had less than 10,000 employees. The ESOPs and aligning the employee’s salary to that of competition during Nayak’s era also showcases employee friendly attitude of the bank.

Strategic Asset

The branch, ATM and base of deposit holders, form the strategic assets for the bank.

Case Study: HDFC Bank

HDFC Bank was started by a group of bankers previously working in eminent foreign banks such as Bank of America and Citibank. As of writing the book, the author states that HDFC Bank was the only Indian bank to be featured in the list of top fifty largest banks in the world. The bank is known for its flawless and consistently successful execution. The engrossing journey of HDFC Bank is discussed in three phases.

Phase 1: 1994-99

HDFC Bank was promoted by HDFC Ltd, the mortgage financing company. HDFC was amongst the first private banks in India and received the banking license in 1994. Now the task of Deepak Parekh, the then managing director of HDFC was to find a suitable leader to head the bank and make it a success. He zeroed in on Aditya Puri, but bringing him back to India leaving a well-paying stable job at CitiBank Malaysia was quite a task.

Puri was also very adamant to build the bank on his own terms. He brought some well-known talent from CitiBank and Bank of America, incentivizing them with the opportunity to build a bank from scratch and of course working under the banking and financial services veteran Aditya Puri and Deepak Parekh respectively. Puri’s ability to influence Parekh was so much as he even forced him to keep the name of the bank as HDFC Bank instead of Bombay Bank as thought of by Deepak Parekh. He thought so because starting a bank was a risky venture and did not want to harm the image of HDFC brand if the bank was unsuccessful. But Puri being himself, threatened to abandon the plans altogether if he did not get the name. HDFC brand of course gave the bank a head start.

HDFC bank is known as a retail banker but what very few of us knew is that it started as a corporate banker. However, the risk averseness was in the blood of these bankers since inception and hence would lend only to the top blue-chip corporates where although the margin was lower but safety was assured.

The strategy behind sustaining even at low margins was getting the cost of raw material (deposits) down. This made HDFC bank think of a novel cheque settlement method for cooperative banks. Earlier suppliers were reluctant to accept cooperative bank cheques as they would have to pay extra to their banks in order to get it cleared. Additionally, it used to take 3-4 long days. What HDFC bank did was it issued at par cheques to the cooperative bank customers. These would be given to the supplier and the supplier could encash it through any HDFC bank branch in their respective cities. This saved overhead charges and working capital getting struck. However, in return for this, the cooperative banks had to keep deposits at HDFC bank free of any charges.

HDFC Bank was also the first bank in India to have a centralized system. A centralized system is one where the risk management and key decision-making lies in the hands of the headquarter branch. This reduces the possibility of fraudulent practices at the branch level.

Another remarkable innovation was introducing a real time electronic processing system to replace the manual payment process in the stock exchanges. This got the entire supply chain – investors, brokers, exchanges and custodians into the ambit of HDFC bank. The next step was obvious to launch the loans against securities as a by-product of relations built through it.

What ticked HDFC right in its inception days itself was instead of concentrating on high margin loans, they focused on generating low-cost deposits. This way they had the higher CASA ratio as well as the highest net interest margin in the industry turning into higher return on assets by the end of first phase itself.

Phase 2: 2000-08

Till now HDFC was a corporate bank. However, they were well aware of the opportunities in retail banking. Hence by 2000 they started being aggressive in this area. However, rather than concentrating its resources on expansion of branches and ATMs (like Axis Bank), they instead concentrated on providing superior technology and solutions to its retail clients. Therefore, the bank became the first Indian bank to launch mobile banking in the year 2000. By 2003, they launched credit cards and two-wheeler loans. Over the coming years the bank had expanded to a number of areas in retail banking, however, home loans were still a missing piece. They could not start this business as it would be a conflict of interest with its promoters, “HDFC Ltd ''. Therefore, they tried instead to become a distributor of HDFC’s home loans for a fee of 0.7%. The arrangement was so successful that, by FY15, HDFC Bank originated one-fourth of the total loans disbursed by HDFC.

The next expansion strategy was selling third party products like mutual funds and insurance and also acquiring point of sale terminals to earn a fee every time a card was swiped.

Phase 3: 2009-16

Aditya Puri was a very big believer in the rural and semi urban areas in India which inhabited 70% of the population. They had built a strong rural franchise helped by the acquisition of Centurion Bank of Punjab.

This was also a testing time for the loan quality for Indian banks. The shocks that started from Lehman Brothers in the US had its trembles felt even in the Indian lending market. Most Indian banks, public or private faced NPAs or lack of recoveries of the loans. However, for HDFC Bank there were no such instances. For them it was mostly business as usual. During the FY09-15 period, HDFC bank was able to grow its retail loan book at a CAGR of 20% in comparison to 13% industry growth.

This period also marked the digital expansion of the bank. Puri was of the view that since the bank already was a market leader in retail loans, payment business and advisory business, why not disrupt it using technology to remain the market leader in the future as well. Puri is said to even visit Silicon Valley to understand how fintech is disrupting the banking space. In FY15, HDFC bank launched a slew of products like mobile wallet PayZapp, ten seconds pre-approved loans, among many others.

IBAS Framework:

Innovation

HDFC Bank can be titled as a pioneer in bringing many technological revolutions in how we do bank today. The centralized banking system was one of the major innovations of the bank. The other innovations were real time processing for stock exchanges, mobile banking, ten-second loan disbursal process, and many others.

Brand

The story of how HDFC Bank got its name has already been discussed. The reputation of the HDFC brand can be felt by the eagerness of Puri to keep the name of the bank on the mortgage lender itself. The bank is also said to spend very less on marketing in comparison to other private sector banks. They have also been endorsed by celebrities like Axis Bank and ICICI Bank.

Architecture

The consistency in financial outperformance is a result of the strong internal architecture of the bank. The bank has fixed allocations for each of its segments in order to control the risk for the overall bank. The bank has a well established process and hence is sometimes even called an SOP bank.

Strategic Assets

The branch network, ATMs and 25 million retail saving accounts remain the strategic assets of the bank.

Case Study: Astral Poly

The story of Astral Poly is about Mr Sandeep Engineer, who started his professional journey with a salary of ₹ 850 a month in the year 1981 to build up a 4,886 cr market cap company in the year 2016. Like all other companies described in this book, here too, the company was a pioneer of CPVC pipes that we use in our homes today. The company now has a 70% market share which quite unbelievably was on the cusp on bankruptcy in its initial years itself. The story of this company is divided into three phases.

Phase 1: 1997-2003

The Chinese proverb “Fall down seven times, stand up eight times'' is the basis of the story of Astra Poly. The promoter, Sandeep Engineer (henceforth referred to as Engineer), has seen a lot of struggles that ultimately made him stronger and stronger.

The story of his entrepreneurial journey started with a pharmaceutical business which was ultimately shut down due to the collapse of its biggest customer. Then he incorporated a bulk drugs manufacturing company that was also closed down due to strict government regulations. In 1991, he started Kairav Chemicals, named after his son, to manufacture Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (API). This business stayed on for a while. However, during this time itself, Engineer started becoming fascinated towards CPVC which could survive high heat (200-degree Fahrenheit). He decided to partner with Lubrizol (the company that held the patent for CPVC resin which is the raw material for CPVC pipes) and bring CPVC to India.

He travelled to the US in order to form a joint venture (JV) with Thompson Plastics. This was in order to gain the know-how for setting up the CPVC plant. After acquiring the license from the patent holder, he set up Astral Poly Technik in 1996. The initial capital was funded as follows: 20% by the JV partner (Thompson Plastics), 20% by Engineer’s uncle and the balance 60% by Engineer himself. He had sourced the money by selling his ancestral house in Ahmedabad.

The company started by launching industrial pipes as a replacement of (Galvanized Iron Pipes) GI pipes which were prone to corrosion. The product however was 20% costlier than the GI pipes. This was a major deterrent for the product’s initial pick up.

This proved to be a risky venture for Engineer. He had an established business “Kairav Chemicals” which was used to fund Astral. However, soon after the 2001 Gujarat earthquake jeopardized the Chemical business as well. Added to his troubles, the main banker to Astral, “Madhavpura Mercantile Cooperative Bank” also failed which resulted in a liquidity crisis for the company.

In 2003, Astral was on brink of bankruptcy.

Phase 2: 2003-06

Engineer had to do something to save his brain child. He was already all-in for the CPVC business and had no other equity left to save the company himself. Therefore, he travelled to Alabama to convince the Thompson family to convert the loan into equity and infuse some money in order to generate capital for capex. They agreed.

This embarked on a turnaround for Astral. Engineer realized that the industrial segment was difficult to tap. Therefore, he shifted his focus to CPVC pipes used in plumbing. Engineer started to approach real estate developers and hotels to use these pipes instead of copper pipes. In 2003, he received his first large order from a south Mumbai based real estate developer. Once the product was in the market, many other popular real estate developers in Mumbai like Hiranandani and Kalpataru also joined in as customers for CPVC pipes. Soon developers in other cities followed.

Now he wanted to get into the retail market as well. Here Engineer realized that the key decision maker was the plumber and hence he gave his focus to market Astral’s products to the plumbers.

As the business stabilized, the company could also spend large amounts on advertisements and chose two hindi channels, Aaj Tak and Star News. In the fifteen years since he started Astral in 1996, the firm grew rapidly to become two-thirds the size of the largest plastic pipe manufacturer in India—Supreme Industries. To put things into perspective, in FY06, Astral generated net revenues of ₹ 51.8 crore from its HP plant, higher than the Rs 45 crore of revenues generated that year from its Gujarat plant.

Phase 3: 2007-15

Now CPVC was held as a reliable product and Astral was serving big real estate developers, public sector and large companies in the private sector as well. After establishing scale, Engineer’s challenge was to build a pan-India brand. Unlike a Bajaj Auto or a Hindustan Unilever, Astral’s target group was not the end-consumer, but the humble plumber who Engineer knew exercised considerable influence in choosing pipes. While the first wave of advertising in 2004 had provided awareness, the next wave would have to entrench Astral as a brand in pipes. He chose Lowe Lintas as their ad agency and in August 2014 announced that Bollywood superstar, Salman Khan, would be its brand ambassador. Khan’s superhit movies included Dabangg in 2010 and its sequel Dabangg 2 in 2012.

The growing strength of the brand also allowed the company to drive bargaining power with its dealers and hence they reduced the debtor days from 43 days in FY14 from 96 days in FY07.

The phase also accompanied a mistake wherein the company established its operations internationally in Kenya. This however didn't work out as planned but the capital employed was very small, less than 1% of the company's capital.

IBAS Framework:

Innovation

The company’s main product, i.e. CPVC pipe itself was the major innovation as it was the first product of its kind in the market. The product was better than the already present copper and GI pipes and hence with some effort on marketing and taking lower margin or losses in the initial years, the company was able to succeed.

Brand

The company gave serious attention to brand building as seen with some high-profile TV advertisements along with movie endorsements (Dabangg series). The company was also seen marketing the brand at the last match of Master Blaster in the year 2013. The company has been consistently spending 1-2% of sales on marketing.

Architecture

The company chose a different path and recognized that plumbers were their ultimate target market instead of consumers. Therefore the company made efforts to introduce new products to the plumbers directly.

Strategic Assets

The pan India manufacturing network remains the main strategic asset for the company. Astral’s second strategic asset is its relations with global majors. Lubrizol, a company owned by Warren Buffett, is the pioneer of the CPVC compound globally. Astral is one of the two manufacturers (Ashirvad being the second) in India with access to CPVC technology from Lubrizol. The company’s tie-up with Lubrizol enables it to produce best-in-class CPVC pipes and also launch new products ahead of competition.

The Final Checklist

Saurabh Mukherjea has provided us with a checklist. However, he has cautioned us to not expect a company to be the next ten bagger if it satisfies these provided criteria. However, it is destined to be a great company.

1. Industry Attractiveness

- Is the company’s business heavily dependent on government regulation?

- How many competitors are present in the industry and how strong is the competitive intensity?

- What is the overall size of the industry and its growth potential?

- Is the company in an industry where the proportion of value addition is high?

- What is the capital intensity and capital efficiency of the industry?

- Is the industry’s business dependent on India’s overall business cycle?

- Does the business generate excess returns for the shareholders?

Mukherjea looks for industries which are relatively free of regulation, low on competitive intensity and growing at double-digit rates (examples include heavy trucks, cars, speciality chemicals). Such industries usually tend to have a small number of relatively large companies and in such situations, the top two players in that industry are usually able to generate ROCEs in excess of the cost of capital.

2. Management Quality

- Does the management have a track record of good governance and clean accounting?

- Does the owner of the company have connections to political parties?

- Does the company have a strong track record of efficient capital allocation?

- Do the promoters have a track record of remaining focused on their core operations?

Mukherjea looks for management teams which maintain a clean set of accounts and allow genuinely independent directors (who can look after the interest of minority shareholders) to sit on the board. He looks for promoters who are humble, hard-working, self-aware of their limitations and are focused on the well-being of their business. He is keen to avoid promoters who build business relationships with politicians.

3. Competitive Advantage

- What is the company’s track record on innovation?

- What is the company’s investment in brands and reputation?

- How strong is the company's architecture?

- Does the company own any strategic assets?

- Does the company have ROCEs that are higher than the industry average?

Mukherjea looks for companies which can sustainably drive ROCEs in excess of 15% and in excess of the industry average by deriving sustainable competitive advantages from: (a) a culture of innovation; (b) strong brands; (c) architecture, i.e. unique relationships between people within the firm and/or between the firm and its suppliers or customers; and (d) strategic assets such as intellectual property, physical property or licenses.