Introduction

The hype surrounding blockchain has reached a fever pitch and shows no signs of slowing down. The primary reason is that blockchain has the ability to reduce a lot of efficiencies in how information is created, shared, accessed, and secured. Given its massive potential, it is often compared to the Internet Revolution that started in the late 1990s. However, it is important to state upfront that all that glitters is not gold. Similar to the early days of the Internet Revolution, blockchain also has many “me too” players who perceive the technology to be a one-size-fits-all solution when it is clearly not.

Blockchain is often explained with extensive jargon and buzzwords. In reality, for the most part, the concept is quite straightforward. It only gets tricky when the technology is implemented, and new use cases are built around it.

So let’s get straight to it—what is blockchain, and why does it matter?

- Blockchain is basically a database.

- Blockchain is a distributed database.

- Blockchain is (arguably) a crowd-managed distributed database.

- Blockchain is a crowd-managed distributed secure database.

As you may be aware, a database is essentially a collection of information stored in systems and servers for easy accessibility. Some databases that we come across in our daily lives are centralised in nature, i.e., they are stored and managed from the same location. For example, a library’s database for books and customers is only located on its server. On the other hand, Blockchain is a distributed database which means that the information is kept on multiple servers (called nodes) across different locations. Each node will have an identical copy of the blockchain, and any updates will be reflected on all of them. Therefore, even if one node malfunctions, others can continue working normally.

The term crowd-managed stems from the database being distributed between regular people like you and me working on our personal computers. It is often referred to as a peer-to-peer (P2P) network. Fundamentally, no authority or group is in control, although the reality may differ at times. The security and superiority of the blockchain will become apparent after understanding how it works.

How Does Blockchain Work?

Previously as we have been introduced to the concept of Blockchain, now let us learn how it works. So, let us get started:

Any information or transaction on the blockchain is known as a record. So, if I give you a payment of $20, all the transaction details will form a part of the record. The different nodes check this record and certify its validity. Only if a majority of the nodes (at least 51%) on a network give their approval, called consensus, then only the record is added and stored in a block.

It is important to note that the blockchain is sequential, meaning that every block is linked to the one preceding it. Therefore, apart from containing the record, each block carries its own unique hash and the hash of the previous block’s data. In simple words, the hash is created through a math function and generates a unique alphanumeric string. You can compare the concept to a thumbprint scan which is distinct for every person.

The interesting thing about a hash is that even the smallest change in the original information will generate a new hash. Therefore, if someone were to tamper with the data, it would be reflected in the hash. Since every block is linked to the previous one, hackers will not get their way unless all hashes are re-calculated and changed throughout the blockchain (which will require stupendous computing power). Additionally, as suggested earlier, unless a majority of the nodes verify the block's validity, it is not added. Since every node has the exact copy of the blockchain, it is virtually impossible to invade all of them. These are the primary reasons why blockchain is considered to be secure and tamper-resistant.

How can a user transact on the blockchain?

To understand the process of creating a transaction, we have to dive into two simple concepts under cryptography, i.e., public and private keys. Everyone that is a part of the blockchain has access to both these keys, and just like hashes, they are also randomly generated alphanumeric codes. As the names suggest, a private key is meant to be secretive and held by the owner, while the public key is visible to everyone.

Using someone’s public key makes it possible to encrypt a message such that only the person with the corresponding private key can decrypt it. The most frequently used analogy is that of a mailbox. Everyone knows your mailbox; hence, it is similar to your public key. However, only you have the key to unlock the box and access the mail kept inside it. Therefore, it acts as your private key.

In the context of blockchain, the private key used in a transaction creates a digital signature, which is also unique in nature. It is useful because anyone with the corresponding public key can verify that the transaction was carried out by the owner of the said private key and has not been tampered with since. When most people in the peer-to-peer network check the validity of the transaction through the public key and reach a consensus, it is successfully added to the blockchain.

How is consensus achieved on the blockchain?

By now, it is evident that blockchain, in principle, is decentralised and dependent on its participants to verify transactions. But how do these participants go about it and reach a fair conclusion? The answer lies in two primary consensus mechanisms—proof of work and proof of stake.

Proof of Work (PoW) facilitates the process of consensus by requiring participants to use computational power and solve cryptographic and mathematical algorithms. This process is called mining. Mining cryptocurrencies requires computers with special software specifically designed to solve complicated, cryptographic mathematical equations. Mining pools may also be used to combine computational power and resources to better solve the problems. To incentivise people to perform these tasks and mine, they have a shot at being rewarded with tokens like Bitcoin. The number of Bitcoins mined depends on available resources. Best functioning computers can do the job in a matter of hours while solo miners can take even a month to mine a Bitcoin. As and when these problems are solved, the blocks are verified and added to the network. Generally, proof of work is skewed towards those with superior hardware and computing power. It also consumes a lot of electricity, given the rate at which the computation takes place.

The Proof of Work makes the database resilient to attacks, as an attacker will need to have control over more than 51% of the network's computing power to tamper with the transactional data.

Proof of Stake (PoS) was developed as an alternative to the PoW mechanism and overcame some of its barriers. In this, participants can stake some digital asset, like cryptocurrency, to earn the right to verify new blocks and add them to the blockchain. The reward for them, in this case, is the transaction fee from the block. While this mechanism seems to favour the rich, it is considered a more viable option.The more validators the network has, the smaller the proportion of the reward will be. Generally, for cryptocurrencies, one can earn anywhere between 5 to 20% per annum on the amount out on stake.

Blockchain is fairly a new technology, and the possibilities are endless as we have learned the basics of how the technology works; going next in this module, we will discuss a few possibilities of potential applications with the help of blockchain.

Potential Applications Of Blockchain

Applications of Blockchain

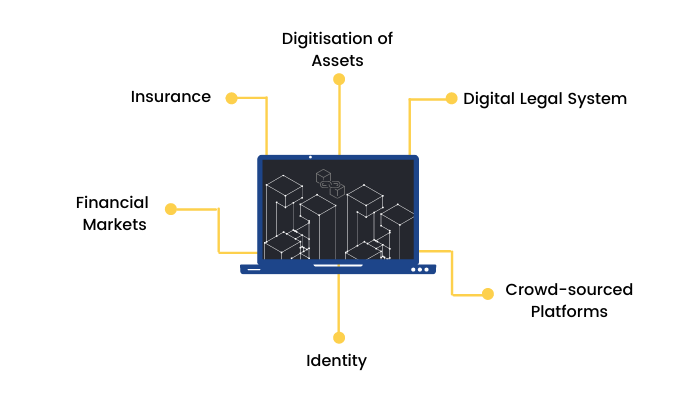

Decentralisation is the core theme of blockchain and the basis of many of its applications. Since it has successfully supported Bitcoin for years (discussed later), it is ready for experimentation in various other industries and use cases, some of which are given below.

Digitisation of Assets

A company or authority or any similar entity typically centralises all asset registrations. What if they could move to blockchain to make it more transparent, efficient, faster and secure? This could apply to many areas, from housing and vehicle registration to authenticating luxury assets like paintings, diamonds with digital certificates.

Digital Legal System

Various legal documents are signed by different parties, stored in a physical or scanned format, and possibly registered with central authorities. They could potentially move to a digital format with standardised or custom contract formats and secure digital signatures embedded within the blockchain itself. Eventually, this may be used to introduce smart contracts, which can be actionable events based on multiple conditions like time, place, etc. For example, a person's will can be written in this format to allow the inheritance of his wealth only upon a certain time or event like his death.

Crowd-sourced Platforms

Many platforms like Wikipedia that are purely crowd-sourced in nature could benefit dramatically from Blockchain’s information creation and management system.

Identity

Digital ID creation for every individual, combining verification under the decentralised blockchain identity systems, can create the world's largest set of unique digital IDs. Various governments around the globe have failed to realise the potential of this use case and are yet to implement it in its entirety,

Financial Markets

Financial institutions, including banks, have inefficient processes and legacy infrastructures to manage transactions. Various post-trade transactions for payments (for example, in banks) and clearing and settlements in the securities world (stock markets) could be dramatically improved using blockchain. But due to high overheads and delays in validating various blocks before the transaction, blockchain may not be helpful in live trading processes for now. This may change as blockchain technology gets more mature, scalable and faster in the next few years.

Insurance

Blockchain can transform the way people manage identities and personal information, leading to a change in the way insurers review risk and price the premiums. Blockchain applications in insurance are likely to start with digital identity systems and the management of personal data. Smart contracts (where the outcome is pre-determined or event-based) can help end-users self administer their insurance policies.

Challenges Of Blockchain

Blockchain is by no means a fool-proof technology; neither can it be applied in industries without a thorough cost-benefit analysis. As mentioned earlier, the cost of computing, energy consumption in mining for transactions becomes very high as the blockchain increases in size. Also, the growing size of blockchain can be a problem as any node will need to replicate throughout the blockchain, which may take a long time.

1. Speed

Currently, the maximum number of transactions supported in the public Bitcoin blockchain is 7 per second, with PoW and other validations in place. In the next few years, it's very likely that we will disrupt blockchain computing, and scale and speed challenges will be resolved.

2. Recourse/Modifications

It is virtually impossible to modify a transaction once it is put in place on the blockchain. While this is a benefit in many cases, the flipside is that even grave errors are fixed. Unfortunately, there is virtually no way to fix anything later deemed incorrect.

3. Private vs Public vs Mixed Blockchains

Public blockchains can scale but make processes slower. On the other hand, private ones can be faster, but then the use case for blockchain needs to be clear otherwise a simple shared database may work. Mixed permission-based blockchains are in relatively nascent stages as of now and will need work to become holistic solutions.

4. Adoption and Integration

The integration and replacement of current systems and workflows is the biggest challenge for any disruption. For blockchain to truly disrupt the ecosystem, consistent efforts need to be made for its correct adoption. Unfortunately, larger institutions like banks working on the same systems for years take time to adapt to any change.

5. Legal Challenges

For any disputes arising from blockchain transactions, there are various loopholes where the existing legal frameworks and courts may not be able to resolve the disputes easily. The legal framework for blockchain is yet to be fully developed in countries worldwide.

Technical Description Of Blockchain

Bitcoin Blockchain

The first blockchain that was built using the principles described by its originator Satoshi Nakamoto in his famous white paper—Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.

Bitcoin (the cryptocurrency)

The digital token on the Bitcoin blockchain that is mined and used as a cryptocurrency. Bitcoin has demonstrated that using a blockchain anyone can exchange digital currencies without a central clearinghouse and without disclosing their identities. Since 2009 when it was launched, Bitcoin has become one of the largest payment systems in the world.

Public-Private Key Encryption

In the early days of the internet, sending private messages was difficult. To send an encrypted message, it would be scrambled using key (also called cipher), and then decoded by the recipient using the same key. The key had to be agreed upon before exchanging the messages, and had to be separately communicated to the recipient before the message itself. Hence if a key were compromised, the encryption stood defeated.

Public-private key encryption overcame this problem by eliminating the need for a shared key, but by using a pair of keys—a widely disseminated public key and a private key. The party sending the message can encrypt it using the receiver’s public key, which can then only be decrypted by the receiver using the private key.

In 1978, a team of cryptographers in MIT developed the RSA algorithm to create a mathematically linked set of public and private keys generated by multiplying together two large prime numbers, since while multiplying them is easy, it is exceptionally difficult to prime factorize the result in reverse. The RSA algorithm enabled people to broadcast their public keys widely, knowing that it would be nearly impossible to uncover the underlying private keys. This then further led to the development of the concept of digital signatures.

Bitcoin relies on public-private key cryptography for people to create their Bitcoin accounts under a digital alias without seeking anyone’s permission. Having created an account, people can then send Bitcoins to anyone in the world by executing and signing digitally a transaction with a private key. Members (or nodes) of the network then verify that the transaction is valid and update the balances of the corresponding Bitcoin accounts by recording them in the blockchain using the Bitcoin protocol—a free and open source software.

Cryptographic Hash

A hash function takes an input value (any data like numbers, files, etc) and creates an output value deterministic of the input value. For any x input value, you will always receive the same y=f(x) output value whenever the hash function f is run. In this way, every input has a determined output. For example, the hash function MD5 (a commonly used function for validating data integrity) creates a 32 character hexadecimal output from any input data:

MD5(”hello world”) = 5eb63bbbe01eeed093cb22bb8f5acdc3

Hash functions are generally irreversible (one-way), which means you can’t figure out the input if you only know the output – unless you try every possible input (called a brute-force attack). Hash functions are often used for proving that something is the same as something else, without revealing the information beforehand.

In case of a blockchain, every new block added to the blockchain database, contains a hash (cryptographic hash) of the previous block, which makes it tamper-resistant. This is because changing any particular transaction in the blockchain database would change the hash of the block being tampered with, which would cascade to all the subsequent blocks added in the blockchain.

Nodes

A node can be a computer or some other network device like a printer which has a unique network address to permit exchange of data. Hence the nodes can create, receive, store or send data along the network routes.

Peer-to-peer (P2P)

P2P implies that there is no central point in the system or network, all nodes act in conjunction with each other to collectively achieve the output. In other words each node can act as a server for the others to allow sharing of data without the need for a central server. All peers are equally privileged.

Block Header

The core of a block’s header is a unique fingerprint or hash of all the transactions contained in that block, along with a timestamp and a hash of the previous block.

Block

Sets of transactions are grouped together into blocks which are then linked together in a sequential time stamped chain using the information in the respective block headers. The entire chain of blocks is then referred to as the blockchain. In the case of the Bitcoin blockchain, each block stores information about transfers of Bitcoin from one member to another.

Protocol (or Protocol Layer)

The protocol is that set of special rules that nodes in a blockchain network use when they transmit or receive information and by which consensus is maintained across the network. A similar example would be the TCP/IP protocol which forms the backbone of communication on the internet itself.

Proof of Work (PoW)

A Proof of Work algorithm (PoW) is how new Blocks are created or mined on the blockchain. The goal of PoW is to discover a number which is the solution to a mathematical problem. The number must be computationally difficult to find but easy to verify by anyone on the network. This is the core idea behind Proof of Work.

In the case of the Bitcoin blockchain, while generating a hash for any given block need not be challenging, the Bitcoin protocol purposefully makes this task difficult by requiring that a block’s hash begin with a specified number of leading zeroes, which constitutes the PoW. Any computer trying to generate a valid hash must run through repeated calculations to meet the protocol’s stringent requirements.

Ultimately, the Bitcoin protocol creates what can be regarded as a “state transition system”. Every ten minutes, the Bitcoin network updates its “state”, calculating the balances of all existing Bitcoin accounts. The PoW consensus algorithm serves as a “state transition function” that takes the current state of the Bitcoin network and updates it with a new set of Bitcoin transactions. Even though Bitcoin lacks a central clearinghouse, users gain assurance that the balance of every Bitcoin account is accurate at any given time. The protocol enables trusted peer-to-peer transactions between people who do not know and hence may not trust, one another. This is why blockchain technology is called a trustless system.

Miners

The nodes which carry out the intensive PoW computations and solve the mathematical puzzle required for them to generate the hash needed to add a new block on the blockchain are usually referred to as Miners. The Bitcoin protocol adjusts the difficulty of the mathematical puzzle depending on the number of miners on the Bitcoin network participating in the PoW game to ensure that a new block gets added approximately every ten minutes. The more the number of miners, the harder it becomes to generate a valid hash with an appropriate number of leading zeroes.

Having arrived at a valid hash, the miner then broadcasts the same to the rest of the network, which re-verify it using a simple calculation at their end, and then adds the block to their local blockchain copies.

Consensus Mechanism and Soft Forks

The Bitcoin protocol incorporates a consensus mechanism that helps members of the network agree on whether a Bitcoin transaction is valid and should be recorded in the blockchain and who owns what amount of Bitcoins at any given point in time. Occasionally, the Bitcoin network soft forks or splits into multiple copies when different portions of the network append a different block to the blockchain. This could happen for different reasons, for example, when an updated version of the client running the Bitcoin network is released, and a number of nodes connected to the network fail to update their software.

When the Bitcoin blockchain soft forks, the database structure turns into a tree rather than a linear chain. To ensure that the network converges towards the same branch of the tree, the Bitcoin protocol implements a fork rule stipulating that in case of a fork, miners should always pick the longest chain — that is, the branch with the most confirmed blocks as measured by computational power required to validate these blocks. This rule enables the Bitcoin protocol to preserve consensus throughout the network. If a majority of the network agrees on a particular chain of transactions, that chain is presumed valid.

Bitcoin holders thus trust that at any given time, those controlling a majority of the computational power supporting the Bitcoin network are acting in accordance with the protocol’s rules, verifying transactions and recording new blocks to the longest chain.

Tokens - Incentives for Mining

To compensate for the cost of engaging in Bitcoin mining, the Bitcoin protocol implements an incentivisation scheme to encourage people to maintain the Bitcoin chain. Every time a miner generates a valid hash for a new block of transactions, the Bitcoin network will credit the miner’s account with a specific amount of a digital native token or Bitcoin—known as block reward—along with transaction fees. Miners on the Bitcoin network thus have an economic incentive to validate transactions and engage in the PoW guessing game.

Because the Bitcoin protocol is only programmed to allocate 21 million Bitcoins, the block reward program progressively decreases over time —halving once every approximately four years from its launch in January 2009 until approximately 2140. Tokens such as Bitcoins thus represent digital assets that have ownership and are transferable.

In general, tokens are digital assets that can be owned and transferred. They can be native tokens of a blockchain like Bitcoins and ether, or tokens of blockchains forked from Bitcoin or Etheruem or others (BitCash, Monrero), or tokens created on a new protocol implemented on top of existing blockchains like Bitcoin and Ethereum (Augur, Gnosis).

Some Keyword Surrounding To Blockchain Industry

Here are some common keywords that are often used in the Blockchain industry:

Initial Coin Offering (ICO)

The process by which blockchain startups offer investors units of a new digital token or cryptocurrency in exchange for cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin or ether. First held in 2013, this method became the rage in 2017, and accelerated in 2018 as the primary way to fund the development of new cryptocurrencies. The pre-created tokens are then sold and traded on cryptocurrency exchanges if there is a demand for them.

Crypto Exchanges

A crypto exchange allows its clients to trade cryptocurrencies with each other or in exchange with regular fiat currencies (a government-issued currency that is not backed by a commodity such as gold). The crypto exchanges set the exchange rates for the various tokens and currencies based on the actions of their sellers and buyers, as well as on the wider market rates on other exchanges as well. However, there can be other factors affecting the price on a particular exchange, since there is no regulatory oversight at all. Exchanges charge a commission on intra-crypto trades and typically a higher fee on crypto-fiat exchanges.

Crypto Wallets (Hot and Cold)

A cryptocurrency wallet is a software program that stores private and public keys and interacts with various blockchains to enable the user to transact with different digital currencies. The wallet software has embedded commands that allow these transactions with each cryptocurrency having its own unique address and commands.

A Hot Wallet holds the private and public keys in storage even as it remains connected to the internet. Hence these are susceptible to cyberattacks or theft. Hot wallets can be computer-based, mobile-based or cloud-based software programs.

A Cold Wallet, on the other hand, is much more secure as it stores the keys offline. It is only when the user wishes to transact with those currencies that the wallet needs to be connected to the internet. These can be independent hardware devices with robust security features which need to be put online through a computer when transacting.

Ethereum

The second-generation public blockchain that, unlike the Bitcoin blockchain, focuses on running decentralized programs called Smart Contracts. Miners work to earn ether, the cryptocurrency token that fuels the network and used by application developers to pay for transaction fees and services on the Ethereum network. There is a second type of token that is used to pay miners fees for including transactions in their block, called gas, and every smart contract execution requires a certain amount of gas to be sent along with it to entice miners to put it in the blockchain.

Application Layer

The topmost layer of the blockchain network where a distributed application resides and executes. Bitcoin’s scripting language enables us to write a script that is recorded with each transaction, allowing us to encode rules to communicate on the blockchain and build applications. Similarly, Ethereum has the Ethereum Virtual Machines (EVM) and its own scripting languages to code applications called Smart Contracts on the blockchain. Hence the complete stack may be viewed as:

- Application (application layer)

- Token (reward layer)

- Protocol (communication layer)

- Blockchain (database layer)

Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM)

The Ethereum protocol processes transactions and smart contracts using what is called the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM). Every node that is participating in the Ethereum network runs the EVM, and hence it is computationally intensive. To compensate for this, and to incentivise the nodes (or miners), the protocol allows the miners to charge a small fee referred to as gas.

Transactions originate from externally owned accounts, whereas messages originate from contract accounts. Both transactions and messages are objects containing a particular quantity of ether, an array of data, the address of the sender, and a destination address. For transactions the destination address can be either another contract account or an external account, whereas for a message it can only be another contract account. Hence messages allow contracts to call one another.

Anyone can trigger the execution of a smart contract by sending an ether transaction to the corresponding contract account. When a contract receives a message, it has the option of returning a message to the original sender just like a standard computer function.

The price of gas is not fixed but is dynamically adjusted by miners based on the market price of ether. Because all active nodes on Ethereum run the code of every smart contract, the code is not controlled by—and cannot be halted by—any single party. A smart contract thus operates like an autonomous agent, automatically reacting to inputs received from externally owned accounts or other smart contract programs executed on the network.

Proof of Stake (PoS)

Proof of stake is an alternative process for transaction verification on a blockchain. Unlike the proof of work system, in which the user validates transactions and creates new blocks by performing a certain amount of computational work, a proof of stake system requires the user to show ownership of a certain number of cryptocurrency tokens. Blocks are not “mined”. In most cases, a fixed number of tokens are created at launch and transaction fees are paid for adding blocks.

In order to validate transactions and create blocks, validating nodes must first put their own tokens at ‘stake’. If they validate a fraudulent transaction, they lose their token holdings, as well as their rights to participate in the future. Once the stake is put up, nodes can partake in the process, and because they have staked their own money, they are incentivised to validate the right transactions.

This system does not provide a way to handle the initial distribution of coins at the founding phase of the cryptocurrency, so cryptocurrencies which use this system either begin with an ICO and sell their pre-mined coins, or begin with the proof-of-work system, and switch over to the proof-of-stake system later.

Delegated Proof of Stake (DPoS)

In a Delegated Proof of stake process for transaction verification on a blockchain, all nodes vote to elect a limited number of nodes who they trust to validate transactions on their behalf. This speeds up the consensus mechanism without sacrificing decentralisation. The voting is an ongoing process and the elected nodes can be replaced anytime if the others deem them untrustworthy. Like in PoS processes, loss of income and reputation act as incentives against malicious behaviour.

ERC20 Token Standard

Ethereum can be used as a platform to launch other cryptocurrencies on the back of its ERC20 token standard. ERC20 has emerged as a significant Ethereum token and is used extensively in smart contracts. Other developers can issue their own versions of this token and raise funds though ICOs.

ERC721 Token Standard

Ethereum has also created the ERC721 token standard for tracking unique digital assets, such as digital collectibles, and allows for people to prove ownership of scarce digital goods.

Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (DAOs)

Ethereum can also be used to build Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAO). A DAO is a fully autonomous, decentralised organisation with no single leader. DAO’s are run on a collection of smart contracts written on the Ethereum blockchain. The code is designed to replace the rules and structure of a traditional organisation, eliminating the need for people and centralised control. A DAO is owned by everyone who purchases tokens, but instead of each token equating to equity shares & ownership, tokens act as contributions that give people voting rights.

Distributed Ledger Technologies

Distributed ledger technology uses independent computers (nodes) to record, share and synchronise transactions in their respective electronic ledgers, instead of keeping data centralised on a server as in a traditional ledger. The blockchain is one example of this technology.

Now that we are accustomed to common keywords of blockchain technology. In the next unit, let us now understand Bitcoin, which is one of the most popular cryptocurrencies of all time.

Bitcoin Simplified

Say you’re planning a cross-continental trip to three different countries. The usual hassles accompanying such a trip would be the exchange of currencies and the inevitable fee that accompanies each exchange. Say you run short of cash and now need to head to the nearest ATM, and pay ridiculously high international transaction fees.

Frustrating, right?

Now imagine an alternative scenario- one where you don’t need to convert your currencies, travel with actual cash in your wallet, or pay any fees to use it. Sounds like a dream, right? Well, this may very well be the future of money- thanks to a unique little invention called the Bitcoin.

What is Bitcoin?

Bitcoin has garnered a lot of international attention over the past few years. It is a virtual currency that is created and held electronically, and can be used at Starbucks to buy a cup of coffee, or even at Tesla Motors to buy their latest Model S automobile. Barely 8 years old, this revolutionary new-world currency was created by an anonymous person under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto in 2008. Nakamoto subsequently disappeared in 2011. Earlier this year, his identity was claimed by Australian businessman Craig Wright, but he later proved to be a fraud. The true identity of Nakamoto is still unknown.

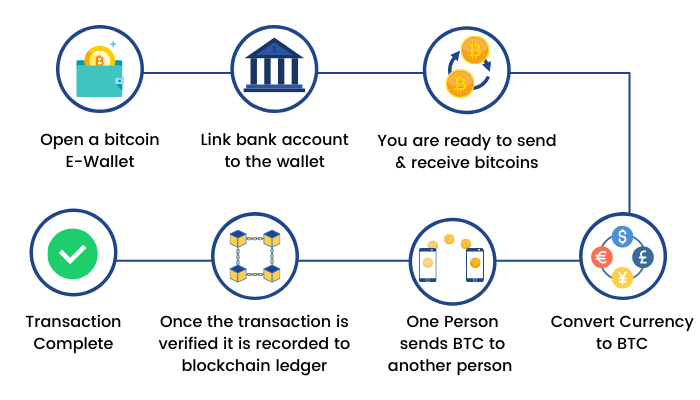

Bitcoins do not have a physical existence and aren’t printed, or minted as coins, which allows them to offer a level of security unlike any other. They are nearly impossible to steal- unless you share your private user details of course. Bitcoin users need to create an e-wallet, which is basically the virtual equivalent of a bank account. It is a software program where Bitcoins are stored, and there are three kinds of e-wallets- desktop wallets, app-based mobile wallets and online wallets.

How does Bitcoin work?

Bitcoin users start off by creating an e-wallet. The virtual equivalent of a bank account, an e-wallet could be a software program or a mobile app. Once you have created an e-wallet, you are ready to send and receive bitcoins. Bitcoins uses peer-to-peer (P2P) technology to operate, and the issuing of Bitcoins is carried out collectively by the public Bitcoin network. The process of adding transaction records to the public Bitcoin ledger is called Bitcoin mining. This ledger is called a Blockchain-as it is made up of a chain of blocks of all the earlier transactions. This allows the highest possible level of transparency possible, as anyone can view the Blockchain online at any given time of the day.

Computers around the world “mine” for coins by competing with each other. By allowing nearly instantaneous P2P transactions anywhere across the world, the Bitcoin allows exciting uses that could not be covered by any previous payment system.

Bitcoin is also unique as a payment system in that it is open-source. In other words, nobody owns or regulates it. The system is, in fact, based on software that uses mathematical logic to create, regulate and transfer bitcoins from the buyer to the seller. Such an arrangement, in turn, results in negligible transaction cost and complete transparency. Think of a banking system minus any regulators such as the Federal Reserve in the US or the RBI in India. However, the decentralised nature of Bitcoin and the freedom it enjoys in terms of regulation have become decisive factors for countries across the world to determine the extent of acceptability of this electronic payment system.

The Evolution Of Bitcoin

As you saw earlier, Bitcoin has come a long way here since 2009. Let us discuss here the evolution of Bitcoin till now.

The Rise 2009-16

In the early days, Nakamoto is estimated to have mined 1 million bitcoins, before disappearing and handing over the reins to developer Gavin Andresen who then became the bitcoin lead developer at the Bitcoin Foundation.

At that time, it was still possible to mine bitcoins using the CPU of any basic computer, and between 2009-10 many early bitcoin adopters were able to amass a lot of bitcoins this way. Then GPUs (Graphic Processing Units) became the new standard for mining and thus began the acceleration of the bitcoin mining race. GPUs are specialised processors that were originally designed to accelerate graphics rendering. Their advantage is that they can process many pieces of data simultaneously. Around 2011, some miners started switching from GPUs to FPGAs (Field Programmable Gate Arrays), after the first implementation of Bitcoin mining came out in Verilog (a hardware design language that’s used to program FPGAs). FPGA is an integrated circuit that can be programmed by a user for a specific use after it has been manufactured. FPGA mining was a rather short‐lived phenomenon, and whereas GPU mining dominated for about a year or so, the days of FPGA mining were far more limited—lasting only a few months before custom ASICs (Application Specific Integrated Circuits) arrived. Now bitcoin mining is heavily centralised and monopolised by large mining facilities around the world, especially in China. Each new block earns its miner a reward, which started off at 50 bitcoins in 2009 and was programmed to halve every four years, and is currently at 12.5 bitcoins, or around US$ 80,000. These block rewards are the only source of new bitcoins in the system.

The first bitcoin transactions were between individuals on the bitcoin forum, and someone paid 10,000 BTC to indirectly purchase two pizzas delivered by Papa John’s Pizza. It was a matter of time before the idea to establish a market platform for trading bitcoins like any other currency would arise, giving rise to bitcoin exchanges — the first cryptocurrency exchange platforms. One of the earliest of such platforms was Mt. Gox which was established in 2010. A major contributing factor to bitcoin popularity around this time were activities of the “dark web”(parts of the internet that are encrypted and not typically indexed by search engines)— services like Silk Road, AlphaBay, and Hansa — all marketplaces for illicit and illegal items. Bitcoin was a popular currency on these platforms due to its anonymous nature.

In the spring of 2011, the price of bitcoin was pegged around $2 when some people began investing heavily in it. WikiLeaks and other organisations began to accept bitcoins for donations in June that year, while in September, Vitalik Buterin co-founded the Bitcoin Magazine. Things picked up momentum in 2012 as BitPay reported having over 1,000 merchants accepting bitcoin under its payment processing service, and WordPress too started accepting bitcoins.

February of 2013 saw bitcoin-based payment processor Coinbase report a sale of over US$1 million worth of bitcoins in a single month at over $22 per bitcoin. The Winklevoss twins Cameron and Tyler, who famously sued Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook, bought $11 million worth of bitcoin. By then the price of bitcoin was $110. More people were putting six-figure and seven-figure sums into the bitcoin market and driving up the prices. Two companies, Robocoin and Bitcoiniacs, launched the world’s first bitcoin ATM on October 29, 2013, in Vancouver, BC, Canada, allowing clients to sell or purchase bitcoin currency at a downtown coffee shop.

Chinese internet giant Baidu allowed clients to pay with bitcoins. The Internet Archive announced that it was ready to accept donations as bitcoins and that it intended to give employees the option to receive portions of their salaries in bitcoins as well. In November, the University of Nicosia announced that it would be accepting bitcoin as payment for tuition fees, with the university’s chief financial officer calling it the “gold of tomorrow”. Around that time, the China-based bitcoin exchange BTC China overtook the Japan-based Mt. Gox and the Europe-based Bitstamp to become the largest bitcoin trading exchange by trade volume. But on December 5, the People’s Bank of China prohibited Chinese financial institutions from using bitcoins, and Baidu no longer accepted bitcoins for its services. Overall, from mid-2013 to mid-2014, China went rapidly from a negligible share of bitcoin trading to virtually the entire market.

Bitcoin’s early history coincided and got forever embroiled with that of the Silk Road — an online black market founded in early 2011 and a part of what came to be known as the “dark web” — dealing in illegal drugs, contraband and merchandise. Bitcoin became the sole mode of purchase on the Silk Road which hit an annual turnover exceeding $15 million, and by the time the FBI cracked down on it in late 2013, huge seizures of bitcoins were made from its accounts. It cemented the “bitcoin is for criminals” image in the minds of many. Even after the dismantling of Silk Road, numerous dark market copycats sprang up using bitcoins as their mode of payment.

In Sep 2014, TeraExchange, LLC, received approval from the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission “CFTC” to begin listing an over-the-counter swap product based on the price of a bitcoin, marking the first time a U.S. regulatory agency approved a bitcoin financial product. In December, Microsoft began to accept bitcoin to buy Xbox games and Windows software. In January 2015, Coinbase raised US$ 75 million as part of a Series C funding (one of the stages in the venture capital raising process, typically the third or fourth round of investment), the highest ever for a bitcoin company. Barclays announced that they would become the first UK high street bank to start accepting bitcoin.

The period from 2014-16 remained one of Chinese hegemony over bitcoin in spite of their government’s clampdown banning their banks from engaging in bitcoin transactions. This could be attributed to the Chinese dominance of bitcoin mining wherein miners would have to sell their newly-minted bitcoins.

By spring 2016, a huge chunk of the bitcoin market shifted to Japan when its government recognized virtual currencies like bitcoin officially in March that year. The Japanese Yen became bitcoin’s biggest trading partner, a lead it still maintains. Uber announced the use of bitcoin in Argentina. By September, there were over 771 bitcoin ATMs worldwide. Swiss Railways (SBB) upgraded their ATMs to be bitcoin compatible.

The Boom 2017-18

On August 1, 2017 bitcoin hard-forked into two derivative digital currencies, the bitcoin (BTC) blockchain with a 1 MB blocksize limit and the Bitcoin Cash (BCH) blockchain with a 8 MB blocksize limit. The size of a block equals the amount of data it stores and the largest amount of data that it can store is the blocksize limit.

Around May 2017, the price of bitcoin (BTC) crossed US$ 2000 for the very first time, rising to US$ 3000 just weeks later. By September, it had scaled past US$ 5000 culminating in an all-time high price of US$ 19783.21 in December 2017, followed by a 30% drop within days. The volatility was, and is, palpable. For most of 2018, its value has ranged between US$ 6000 to about US$ 8000.

Analysts have attributed many overlapping causes for this boom—from outright speculative mania, to a general mistrust in governments across the world, to anti-institutional investors and to hedgers trying to protect themselves against a repeat of the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. The political environment of the US in particular, under President Trump, has also been cited as a major cause, as is the thesis that the generational shift has played a huge role with Millennials showing higher interest in bitcoins rather than in owning stocks. While there are any number of naysayers pronouncing that the bitcoin bubble is ready to burst, there are as many who believe that the boom has a long way to go, and that this is just the beginning. In fact, there is even a special term for bitcoin hoarding by believers and fanatics—HODL—or hold on for dear life.

Bottomline

In hindsight, no one could have imagined that people all over the world would give away real money for a digital currency whose network nobody owns, no central bank guarantees it, is not backed by gold or any other asset, is not even accepted for most real-world products and services, is actively discouraged by many governments and is lost forever if an account key is lost. There is nothing comparable to the bitcoin in terms of a global currency, and if one considers other similar efforts to have a broad-based multi-national currency such as the Euro in the European Union, it is immediately apparent that such projects take decades of effort, negotiations and cajoling to make them acceptable, and then forever remain at the risk of unravelling, as evidenced by Brexit. In contrast, an unknown Satoshi Nakamoto brought users from all over the world together to trust a non-state / non-gold backed digital currency within just a few years of its inception.

Even as bitcoin flourished—it remains the star cryptocurrency even today—a 17-year-old caused a stir with his blockchain design and its token which he named the Breath of the Gods, or Ether. His design was preceded by the work of yet another man who virtually invented the concept of the Initial Coin Offering (ICO) — a precursor to the frenzy that was in the making. While the following chapter is their story, the ICO boom made bitcoin the default gateway currency to invest in these tokens thus cementing it as their leader.

Busting Some Common Myths Surrounding Blockchain

Blockchain Implies Truth

As suggested earlier, the truth or validity of transactions is done through miners working on thousands of mining nodes. However, miners can collude during this process and carry out malicious transactions that others may not pick up. Although the risk is lower in larger networks, collusion is a strong possibility in private blockchains, such as banks.

It is not just the miners that need to be reliable; blockchain cannot judge if the inputs are factually correct either. For example, fake invoices entered in the system would be considered valid if the blockchain’s conditions are met. “Blockchain is not the magic wand that generates immutable truth”. It’s just a means to an end.

Blockchain is the Ideal Technology

Blockchain enthusiasts believe in the massive potential of this technology, and it is possible, provided that what is on paper is actually practised. We have already seen that cryptocurrencies are centralised in many aspects, and it is valid for blockchain too. This impedes the technology from achieving its true capabilities.

On the blockchain, transactions must be validated through multiple nodes before acceptance. Anyone can add or validate transactions, but the process takes place one at a time. Therefore, it is time-consuming. Users generally have to pay substantial transaction fees to validate their transactions quickly. Those who cannot afford to do so have only two choices—wait longer than others or stop transacting all together. Similarly, mining Bitcoins on the blockchain network is expensive and resource-intensive, which have resulted in the formation of concentrated “mining pools”. These mining pools lead the way and validate a majority of the transactions.

Additionally, any person can suggest updates or changes that need to be made to the blockchain network. In reality, however, they are generally proposed by a select number of developers and commentators, making the process relatively centralised.

Private or Enterprise Blockchains Makes Sense

Among many stakeholders, IBM has been promoting and selling enterprise blockchain use cases. Several banks have formed use cases for blockchain consortiums to improve inter-bank data management, operation process improvements.

For any enterprise to use blockchain internally, or with other enterprises, we have had proven, scalable and efficient technologies for decades, including shared databases (SQL, Oracle, SAP).

Please note that blockchain is an expensive technology in terms of resources, as multiple nodes need to be set up, and multiple entities need to validate all transactions since the beginning (no concept of end-of-day final records, so next day’s transactions begin from next day only and not from the first-ever transaction like in blockchain). Decentralisation, by definition, slows down things and introduces security concerns. For a single enterprise with an already trusted set of internal groups, or a handful of external enterprises, private blockchain will not be the best solution. And for inter-banks transactions, payments, and trade settlements, several existing efficient workflows, platforms, protocols like Swift, FIX, etc., exist and work fine.

As an example, if some bank says that they can reduce the current trade settlement cycle from 2 days to 1 second, they should ask themselves why it is 2 days in the first place. It’s not that they were all waiting for blockchain technology to be invented for solving this problem.

If you do not believe this, ask any bank which announced any use case, proof of concept (years ago), if they actually scaled it further or not. Do you recall reading any such “scaled up transactions by banks” in the press release after the proof of concept announcement? The answer will be in the negative.

Transparency/Digitisation is Best Achieved by Blockchain

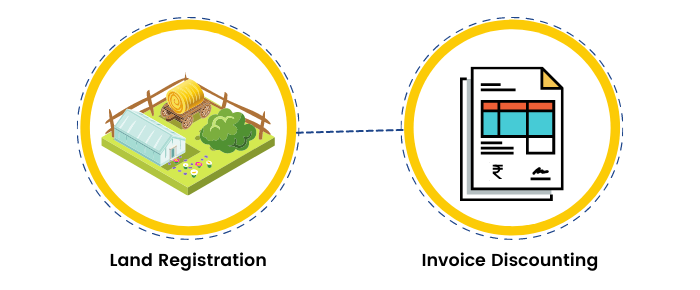

Several POCs or advocated use cases of blockchain are nothing but digitisation of data. Some examples are given below:

- Land Registry: Registry on the blockchain is done by several states and governments while none of them has allowed for independent miner validations, i.e., only states can decide who owns which property and when they approve the transfers. Therefore, it just makes way for online record-keeping instead of offline. Such processes by governments and companies have been digitised for decades without blockchain and more efficiently.

- Invoice Discounting: If a supplier sends an invoice to a client which gets accepted, then they can take, say 70% loan, against that invoice from a bank to develop the products, or get some cash-flow while the products are shipped, say from China to the US, which takes weeks. Typically in such a loan, the supplier, the supplier’s bank, the client and the client’s bank are involved in confirming the transaction, and the supplier's bank gives the loan after that. This approval process can take days.

The challenge in this loan issuance is that there can be fake invoices or companies can take bank loans from multiple banks against the same invoice, or that the counterpart client does not exist. Hence banks are cautious in giving such loans.

Now independent miners are banks’ risk departments who can help validate the authenticity of the transactions. And no bank will open their client data to other banks for validation (in fear of losing the client to other banks). So all that can be achieved is that document transfer between the 4 entities can be made faster from days to hours by using digital signing and digital documents transfer. Such solutions exist and work well without blockchain.

Most problems advocated here are typical digitisation problems that can achieve transparency by making the steps in the workflow public. Think about DHL or any other courier service tracking the package in transit or Uber’s car driver and trip details. People who need to know can know it online very easily, and without needing any blockchain technology implementation.

Blockchain is Efficient

Users have imposed exceptional trust in blockchain technology, but they fail to realise that it is beneficial in some cases, not all. It cannot be blindly implemented across industries. People who make the mistake of using blockchain without a thorough understanding of its consequences might end up with bigger inefficiencies. For example, in private or governmental centralised institutions, a decentralised technology does not fit in. It is the same as a dictator saying that the country is democratic, but only he will vote.

Furthermore, blockchain is expensive to implement and requires computational power, electricity, servers, and related infrastructure. Therefore, blockchain should be evaluated just like any other technology is and see if the benefits are enough to offset the costs.

Blockchain is Tamper-proof

Blockchain is a digital ledger, which means that blocks of information are connected in an unbroken sequence. This sequence is made up of digital signatures that form the blocks, and each block carries the signature of the preceding block. Therefore, changes to one block would require modifications to all blocks in the chain, making the system resilient to tampering.

However, attacks can still occur. For example, if a group of participating individuals control a majority of the network’s hashing power, then tampering might be possible. Hashing power is nothing but the power used by your computer or hardware to run and solve different hashing algorithms This can also lead to a double-spending attack in the case of cryptocurrencies, where high-value transactions can be reversed, and amounts can be spent a second time. To explain a double spending attack, think of money you hold in cash or in your bank. Once you use a part, the transaction is complete and you cannot use it again. However, on the blockchain, since there is no central authority to control transactions, users can duplicate digital files. So, a person can use a copy of a cryptocurrency to make a purchase while retaining the original as well.

All New Discounted IC Tokens Will Rise in Value

ICO (Initial Coin Offering) is the advance sale of a project’s cryptocurrencies or tokens, to be used within their platforms or outside, in advance, to fund the development of their platforms. These tokens can be easily sold and traded at anytime, on all cryptocurrency exchanges depending on their demand. So, an ICO is when a company raises money in Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies for the technical development of their projects. These tokens are essentially the incentives, for several market participants to use and grow the platform in a decentralised manner. Such incentives are paramount in making a decentralised ecosystem operate sustainably. This allows for formation of new economic systems; possibly even capable of transforming/improving wider systems like “capitalism”.

Majority of the ICOs unfortunately don’t and won’t work because:

- Many ideas don’t need blockchain or ICOs at all. They are centralised, don’t need a community, or have no real business models. As explained above, you cannot “decentralise everything”.

- The teams behind ICOs have nothing to lose. Once they raise millions to billions on an idea, basic prototype at best, proven or unproven teams with “self-proclaimed experts” or “larger than life celebrities lending their names”, there is no major pressure to execute their idea well. There is no governance on the use of funds. Compare this to typical startups, where entrepreneurs get modest valuation, and have to be “all in” the project to see any returns after 5-10 years or hard work. They are “on the hook”, forever. And, a lack of regulation, accountability and legality of structures makes it the “wild west“ of finance and reduces the probability of success.

(Mis)Use Cases of Blockchain

Blockchains cannot supplant traditional databases. They have certain admirable features, discussed extensively in this module so far, which makes them an ideal fit for certain applications like crypto-currencies where traditional databases would never have succeeded, and bitcoin is a testimony to that. That blockchains can host and enable decentralised applications and help build open tokenised networks is in itself extremely promising as of now. But almost 99% of our existing digital applications are better off design-wise in their current state and gain next to nothing if they switch their architecture to the blockchain.

Let us look briefly at the deterrents and then at specific use-cases.

First, almost all existing applications (or ledgers) are centralised in control. Replacing a traditional database at the backend with a blockchain does not alter the centralised control, and just replaces a fast and efficient database with a slow and inefficient one. Such blockchains with retained centralised control are being termed as “permissioned” blockchains or private blockchains.

Second, we have already seen that storage costs in a blockchain are very high, because every node stores the full ledger. While sharding in blockchains may ease this problem going forward, it is no match for the storage efficiency of the traditional database.

Third, the transaction processing speed of blockchains makes them appear as slow lumbering giants, unsuited to the super-fast transaction processing needs of the many applications.

Fourth, scaling a blockchain only happens by reducing the number and increasing the power of individual nodes — which is nothing but centralisation in the first place. So why bother?

And last but not least, Blockchain development and execution is costly.

The Smartness of Smart Contracts

The words are deceptive, implying utopian qualities in contracts built on some AI-like magic. The reality is mundane. A smart contract is just a regular program, which reads and writes data from and to the blockchain’s (distributed) database. The code of the program also resides within the same database, so it may be looked upon as the equivalent of a “stored procedure” in traditional databases. Its execution can be triggered by blockchain transactions, thus altering the blockchain’s state. A stored procedure is a Structured Query Language (SQL) code that you can save for reuse in the future. The only additional characteristic is that the code must independently run on every node of the blockchain when triggered, and arrive at a consensus result before the blockchain’s state is altered.

If such a smart contract or program is to respond to external events, the same information must be fetched by every node on the chain, and there must be a guarantee that this information will not alter in the meantime, or the blockchain consensus will fail. That will lead us back to the need for a centralised “oracle” that will guarantee this. Having a trusted entity to manage the interactions between the blockchain and the outside world undermines the goal of a decentralised system, and it’s simpler to have a traditional database at the backend rather than a blockchain.

An oft-cited example of smart contracts is their potential use to automate payment of interest on bonds and loans. But to guarantee such timely payments, the funds must be at the disposal of the smart contract, which would preclude their use anywhere else. In case the funds are at the disposal of any other entity in the system, which they will be because that is the idea behind any bond issuance or loan appraisal, then the blockchain smart contract cannot guarantee timely payment. A stalemate, because a blockchain smart contract cannot transform what is essentially a risky instrument, howsoever low risk, into a risk-free one.

Lately, the media has been chock-a-block with announcements and the launch of blockchain projects across the spectrum. Discussed here are some such projects and announcements where, to a discerning analyst, there is no use-case for the blockchain at all, yet Maslow’s hammer is hitting each one serially.

Banks and Fintech on the Blockchain

The biggest-ticket announcements have stemmed from the banks and the fintech sector where consortiums have been announced to build different versions of blockchains and apps — by “market disruptors” like R3 and Digital Asset Holdings LLC. In 2017, Bank of America Merill Lynch, Wells Fargo, HSBC, Deutsche Bank, HSBC, Reuters and even Intel invested $107 million in R3 product “Corda” blockchain. R3 also announced the integration of their blockchain product with SAP in the case of Commerzbank. R3 then announced another trade finance network “Marco Polo” based on the same Corda blockchain technology but this time including BNP Paribas, ING, Commerzbank, Standard Chartered, DNB and others. Digital Asset, a competitor to R3 raised a $110 million of its own from private investors, and has formed its own consortiums including Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan. The latter is also a member of the blockchain consortium Enterprise Ethereum Alliance as well as the Hyperledger Project of the Linux Foundation. The Wall Street Journal list of top technology companies, dominated by blockchain companies, profiled both R3 and Digital Asset on that list.

Banks claim that they are funding and building these private blockchain networks to settle their transactions more efficiently. Blockchain certainly helps in creating a shared ledger among banks to settle their swaps or other financial product transactions, and save “billions of dollars”. But it’s interesting to analyse why banks spend billions of dollars in these transaction settlements in the first place. It’s primarily due to legacy mainframe systems in the banks’ back offices and workflows that are decades old, need high maintenance to keep running, and are coupled with inefficient manual processes on top. Banks can achieve similar savings if they just replace their back-office systems with any efficient shared database technologies like Oracle, SQL and layer some smart business logic on top of them. Besides, banks’ blockchain networks are private among those that know each other and have several legal contracts between them, and do not need or intend to use any independent mining. Hence, Blockchain serves very little purpose in these scenarios, if any.

Similar is the case of fintech and payment processors. You would be hard-pressed to find one that announced a blockchain use case or proof-of-concept years ago and then actually issued a successful “scaled-up blockchain transactions” press release after the initial announcement.

So should it have surprised anyone when R3 too made its announcement abandoning blockchain technology altogether after spending US$ 59 million on its research? Corda would no longer be based on blockchain, and R3’s altered its description from a “blockchain startup” to a “blockchain inspired startup”. The irony, though, seems to be totally lost on the banks themselves, who continue to pour in funds at record speed.

Real Estate on the Blockchain

Traditionally real estate is driven by paper-based title records and involves a lot of third-party players, including brokers and banks. A blockchain-based design would certainly allow people to transfer funds, property titles and data in a peer-to-peer manner that is digital and open sourced. Dubai Land Department announced the creation of a blockchain based system using a smart and secure database to record all real estate contracts, including lease registrations, linking the dealer, land apartment management companies, phone and internet service providers, furnishing solution providers and even the banks. All this would be done by linking the user’s blockchain profile to his Dubai ID (given by the Dubai government for access to government services) and would contain all remaining information.

Similarly, Deloitte announced the development of a platform to handle rental and other real estate contracts digitally, and invited Commercial Real Estate (CRE) companies and industry participants evaluating an upgrade or overhaul of their current systems to have blockchain on their radar. A third service provider, Ubitquity, announced a blockchain-secured platform for real estate transactions offering a simple user experience for securely recording, tracking, and transferring deeds. The platform prototype was released in March 2016 as a Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) blockchain platform. Ubitquity claimed to provide e-recording companies, title companies, municipalities, and custom clients benefits from a clean record of ownership, thereby reducing future title search time, and increasing confidence/transparency. Citing a Lands Record Bureau in Brazil as one of their early clients, they claim to “use multiple permissioned and permissionless blockchains in an effort to remain fully blockchain-agnostic”.

The problems in this use case stem from the indispensability of paperwork, issues over transparency and time taken to execute transfers. Given that property deals are always going to be approved by some central authority or the other like a Municipal Corporation, or an appointed Government body, the decision making of property transactions shall always be centralised. In such cases, using a technology which touts decentralisation as its chief purpose is antithetical and purposeless. As far as the problem of digitisation of the paperwork and bringing transparency in the transactions process is concerned, this could be easily achieved by digitizing land records, and making the transfer process online where the buyers/sellers can raise their request online and approving agencies can approve it online too. It does not need a blockchain at all. Ubitquity is building on some shaky stilts.

Diamonds on the Blockchain

In the 1971 film Diamonds Are Forever, Bond’s nemesis Blofeld and his SPECTRE organisation use diamond smuggling to fund a space-based laser weapon. In Bond’s 2002 film Die Another Day, his adversary ran an empire on conflict diamonds a.k.a. blood diamonds, something that also fuelled Sierra Leone’s long civil war and insurgency. And there is no heist that excites gangsters more than a diamond heist. So it makes a lot of sense to record a gem on a blockchain recording its provenance and future sales.

Everledger, a startup, claimed to have proven this possibility by logging the identifying characteristics of over 1.6 million diamonds on blockchain, information that would be useful to various stakeholders — from claimants to insurance companies to law enforcement agencies, making counterfeit claims impossible. Little wonder then that IBM also announced TrustChain on its blockchain platform in collaboration with Asahi Refining, Helzberg Diamonds, LeachGarner, Richline Group and Underwriters Labs. Participants in the blockchain network hope to easily keep track of all of the components in a piece of jewellery from the time they are mined, as they’re fabricated into consumer products, such as diamond engagement rings, until they’re sold. Block Verify, another blockchain startup, claims to end counterfeiting and make the world more secure.

The problem in these use cases is the unique identification of assets like diamonds. It's the same problem with paintings (where, for example, an artist draws only five paintings to keep them exclusive and hence priced higher). The challenge arises when people make and sell fake diamonds or fake paintings. What is definitely not being decentralised here is the consensus on what’s original and what’s fake. That shall always be controlled by the firm producing the diamonds or some central authority appointed by the diamond firms, or a curator or museum in the case of paintings. If all they need is a unique digital stamp on each diamond, which could then be easily traced and tracked by the issuer firm, and since such digital stamping mechanisms exist like QR codes etc. are readily available, there is no need for the blockchain at all. We have already discussed the “oracle” problem of blockchains when it comes to physical assets in the Scalability Trilemma, and since diamonds, paintings, and precious jewellery all constitute physical assets, the blockchain cannot track them without a central intermediary to certify that the physical asset in question corresponds to one on the blockchain record. The Scalability Trilemma, in very simple terms, says that there is a trade-off between three important Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) properties, i.e., decentralization, scalability, and security. This effectively nullifies any blockchain advantage, since that very same central intermediary can in any case directly certify the asset in question to be genuine or fake.

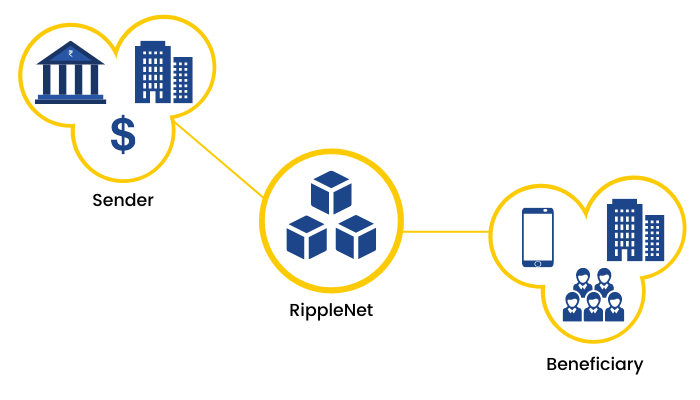

Ripples’ Payment Mechanism on the Blockchain

Ripple has emerged as one of the early-movers and a formidable player in the domain of real-time gross settlement of funds, currency exchange and remittance. It has in a short span of time built a global network of participating banks and payment providers. The Ripple net blockchain network, using the token (cryptocurrency) Ripple (XRP) is meant to enable instant and direct transfer of money between two parties, and the exchange of any fiat currency, commodity or asset.

While the general impression is that Ripple is a permissioned blockchain, that is, a blockchain whose mining mechanism to validate transactions is private and controlled, the truth is somewhat different. As succinctly explained by the Blockchain Magazine:

It is the validating servers and consensus mechanism that tends to lead people to just assume that Ripple is a blockchain-based technology. While it is consensus oriented, Ripple is not a blockchain. Ripple uses a HashTree to summarize the data into a single value that is compared across its validating servers to provide consensus.

Banks seem to like Ripple, and payment providers are coming on board more and more. It is built for enterprise and, while it can be used person to person, that really isn't its primary focus. The main purpose of the Ripple platform is to move lots of money around the world as rapidly as possible.

Thus far, Ripple has been stable since its release with over 35 million transactions processed without issue. It is able to handle 1,500 transactions per second (tps) and has been updated to be able to scale to Visa levels of 50,000 transactions per second. By comparison, Bitcoin can handle 3-6 tps (not including scaling layers) and Ethereum 15 tps.

Ripple’s token, XRP, isn't mined like Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin and many other cryptocurrencies. Instead, it was issued at its inception, similar in fashion to the way a company issues stocks when it incorporates: It essentially just picked a number (100 billion) and issued that many XRP coins.

As a technology, the Ripple platform may have real value and real history that validate the claims they make for its efficacy. The XRP token itself, however, seems to have negligible use cases. In fact, Ripple had planned to phase it out — at least, until fevered interest in cryptocurrencies began to take off in 2016 … The use of XRP is totally independent of the Ripple network in general; that is, banks don't actually need XRP to transfer dollars, euros, etcetera which is what many small investors might be missing when they are buying the token.

Thus, an appropriate way to view Ripple is as a super efficient SWIFT network rather than as a breakthrough application for the blockchain (SWIFT is the current global payment transfer mechanism used by banks, known to be slow and cumbersome). Often touted as one of the most successful examples of blockchain implementation, it is anything but, since it is not blockchain based in the first place.

Some More (Mis)Use Cases

Although we have discussed a few misuse cases of blockchain, here are some more misuses cases surrounding travel, supply, shipping industries and more.

Travel on the Blockchain

The Amadeus IT Group, owners of Amadeus, the largest global distribution system (GDS) for airlines tickets worldwide, recently announced their foray into the blockchain space, stating that it would make travelling easier and streamline the process of making payments, verification of traveller IDs, luggage tracking etc. by reducing the intermediaries and settlement timing while increasing the overall flow transparency. Fast, secure and a simplified ID verification of travellers at every stage seems to be the primary use case for a blockchain.

The fallacy, once again, is that the blockchain is serving no real purpose, because this problem of ID verification at different stages can be solved simply by sharing pre-approved tokens access among the different entities constituting the value chain. It is very similar to the way when you login to many different websites using your Google login which involves no blockchain, because there is no decentralisation or consensus involved. If anything, it is the exact opposite.

Supply Chain on the Blockchain

Project Provenance Ltd. has built a blockchain platform Provenance—“a platform that empowers brands to take steps toward greater transparency by tracing the origins and histories of products. With our technology, you can easily gather and verify stories, keep them connected to physical things and embed them anywhere online.” IBM and Walmart have teamed up to launch the Blockchain Food Safety Alliance in China in conjunction with JD.com to improve food tracking and safety, making it easier to verify that food is safe to consume. Proper implementation of the ledger could also prove valuable for pharmaceutical giants, which are required by law to maintain the chain of custody over every pill. Skuchain and NTT Data announced their partnership in a blockchain supply chain venture.

These use cases would all suffer identical problems as those of tracking diamonds on the blockchain, especially the oracle problem, which occurs in linking a blockchain to real-word physical products. In any case, tracking of food or any other products in a supply chain, manufacturing process, or even couriers, amazon deliveries and Uber car arrivals are all done on simple online platforms using MIS, or any other basic data technologies at the back end. There is no need for any consensus and decentralisation here, and hence, this does not need a blockchain solution at all. The Walmart announcement, in fact, follows their previously failed attempt in 2006 to launch a system to track its bananas and mangoes from field to store, abandoned in 2009 due to logistical problems getting everyone to enter the data in the system. So what failed on account of data entry is highly unlikely to succeed just because you replace the previous database with a blockchain one.

Blockchain or not, any supply chain solution needs to meet two vital prerequisites — everyone’s participation in the chain, and honest participation at that. The garbage-in-garbage-out (GIGO) principle does not exempt the blockchain. GIGO states that if the quality of data fed to a computer is low, so will be the output. So, if the data being entered is not clean, blockchain in fact compounds the problem since the records are non-editable. Bottomline, it is the human element and compliance that is the bigger challenge in supply chains, not the technology.

Documents on the Blockchain

Bank guarantees are essential in sectors such as real estate, where they represent security for tenants’ leases, or where companies need to demonstrate that they can pay for expensive goods. However, bank guarantees can get mislaid, and clients may find the process of handling them to be too laborious and slow. This is why technology companies are now promising a solution in the blockchain—the Israeli lender Bank Hapoalim and Microsoft announced a collaboration on creating digital bank guarantees based on the blockchain technology. The new process will enable Bank Hapoalim customers to receive security documents in a digital, automated and secure manner, without physically coming to the branch and in a very short process.

This is a classic case of finding a complex solution to a simple problem — that of digitizing documents and signing them online. Several authentication apps for scanning and digital signing exist already. There is absolutely no decentralised consensus needed. A blockchain solution is just an overkill.

Shipping and Insurance on the Blockchain

Another announcement in the supply-chain space, EY has teamed up with Maersk and Microsoft on blockchain-based Marine insurance. When shipping goods from port A to port B, any number of things can go wrong: cargo gets damaged, a congested port delays docking, a storm throws a vessel off course, pirates raid a ship. So shippers buy insurance through a complex jumble of brokers and underwriters to manage the risk to their freight. Ideally, a Blockchain should be an absolute fit for this platform to function, as it will be able to guarantee that all parties - from shipping companies to brokers, insurers and other suppliers - had access to the same database, which could be integrated into insurance contracts.

However, in practice, the information flow and approvals are between a few entities (say the buyer, the seller and two or three banks in the above example). They can already achieve the same by digital signatures while sharing the documents through a digital platform (including a simple email server). No independent mining is needed, or can help in this case, hence a blockchain is certainly not the best solution.

The biggest challenge of a supplier faking an invoice, or taking multiple financings from different banks over single invoice, cannot be solved by blockchain either, unless all potential financiers become part of this network and mine/validate every single transaction; which is a big ask and is unlikely to work in the foreseeable future.

Also, shared databases like SQL and Oracle have existed for decades, and collaboration among different entities in the value chain for validation of such documents has also existed for a long time. If the validation of any documents and information is to be done by a few entities, access control-based data solutions can do the job just fine. Insurers would want to control this workflow and final approvals anyways. Hence, this does not need blockchain at all.

Governance on the Blockchain

Samsung’s win of a contract for a public sector blockchain for South Korea’s government to be put to use in public safety and transport applications, is unlikely to achieve its desired goal due to the two perennial bug-bears of all government processes—a centralised workflow and decision-making. In most scenarios, the functioning of a blockchain is the very antithesis of the working of a government, and a mating of these polar opposites remains a distant dream.

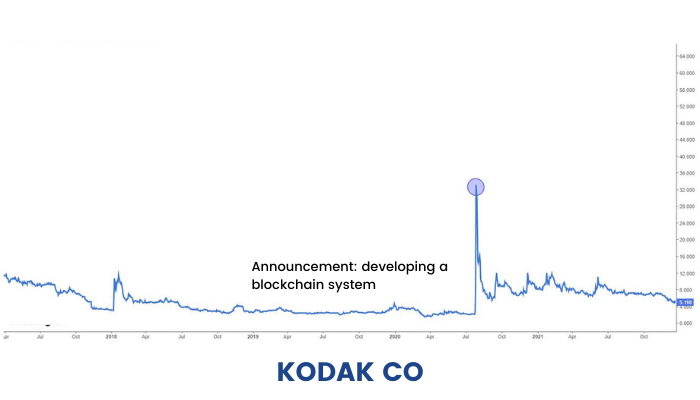

Media on the Blockchain

Kodak recently sent its stock soaring after announcing that it is developing a blockchain system for tracking intellectual property rights and payments to photographers. As one of the oldest names in the imaging business, it is leveraging the blockchain technology to fix problems that have been plaguing the photography industry. Kodak and WENN Digital joined hands to launch a blockchain-powered image rights management platform, dubbed as KODAKOne along with a photo-centric cryptocurrency, known as KODAKCoin. Kodak’s platform takes the whole photography and imaging industry to a new level with the features of distributed ledger technology like encryption, decentralization, immutability, transparency, and security being utilized to create a digital ledger of ‘ownership rights’ for photographers. The digital ledger will secure the work of photographers by registering work and then allowing them to license the same for use (buy/sell) within the platform.

However, the Kodakcoin concept can work only if the coin and the platform are driven by the community. But that will not help Kodak much, as it will not just decentralise itself away as a node. Given that Kodak is not likely to decentralise itself, this use case is only self-serving and the community shall not believe in it. Hence, the blockchain will be infructuous.

Where Does Blockchain Work?